The Congressional Budget Office's analysis of Senate Republicans' ACA "repeal-and-replace" bill found that, thanks to reduced subsidies for premiums and high cost-sharing, "few low-income people would purchase any plan." The newly uninsured would eventually include most of the 15 million enrolled in Medicaid through the ACA's expansion of Medicaid eligibility, which the Republican bill effectively ends.

Why would the bill's creators offer the poor and near-poor health plans on terms that are patently unaffordable? A clue can be found in a lawsuit Republicans have pursued that's gone a long way toward destabilizing the current ACA Marketplace. That suit provides a clue that high cost-sharing for consumers is a feature, not a bug in Republican healthcare plans.

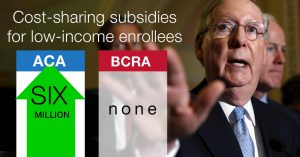

In 2014, House Republicans challenged in court the Obama's administration's authority to pay for Cost Sharing Reduction (CSR) subsidies to low-income enrollees in the ACA Marketplace. One might wonder: What public policy goal could cutting off funding for those subsidies possibly fulfill?

On one level, Republicans simply wanted to hobble the ACA Marketplace by any means available. The opportunity was there, thanks to a drafting error by the ACA's creators – who budgeted for the subsidies, and mandated that insurers provide them to those whose incomes qualified them, but left it to Congress to appropriate the annual funds to reimburse the insurers.

The suit has enabled President Trump to sabotage the Marketplace, since it's up to Trump whether to continue to fight in court for his right to keep paying the subsidies, or to push his party in Congress to appropriate the money. Insurers, who are obligated to provide CSR subsidies to qualifying enrollees whether the federal government pays them or not, have directly attributed the bulk of their requested steep premium hikes this year to uncertainty over CSR payment. Republicans' legal Hail Mary was thus a wild success – if your idea of success is to render healthcare more expensive for millions, and unaffordable for many.

'Skin in the game' – or a pound of flesh

In a real sense, that is the Republican idea of success, and from that perspective, the attack on cost-sharing subsidies is ideologically fitting. Republicans are literally opposed to cost-sharing reduction – that is, to reducing the share of costs paid by patients. If we all have "skin in the game," according to conservative healthcare theory, we'll be smarter shoppers and drive down prices for medical treatment. Republicans don't profess to want each of us to pay more for our medical care in absolute terms, but they claim that if each of us had to pay a larger share of our medical costs, our consumer activism would drive those costs down.

In a real sense, that is the Republican idea of success, and from that perspective, the attack on cost-sharing subsidies is ideologically fitting. Republicans are literally opposed to cost-sharing reduction – that is, to reducing the share of costs paid by patients. If we all have "skin in the game," according to conservative healthcare theory, we'll be smarter shoppers and drive down prices for medical treatment. Republicans don't profess to want each of us to pay more for our medical care in absolute terms, but they claim that if each of us had to pay a larger share of our medical costs, our consumer activism would drive those costs down.

The bill Republican leadership introduced in the Senate last week – repealing large chunks of the ACA and severely cutting federal Medicaid spending – reflects this. The so-called Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) ends CSR subsidies, which reduce out-of-pocket costs for about 5 million current low-income ACA Marketplace enrollees to levels below those of most employer health plans. (Another million-odd enrollees get a much weaker level of CSR.) The Senate bill also phases out federal funding for the ACA Medicaid expansion, which has given 15 million poor and near-poor enrollees access to healthcare with no deductibles and little to no copays.

Affordable – by what definition?

For those it kicks off Medicaid, and for those currently enrolled in Marketplace plans with strong CSR, the BCRA does offer coverage that's "affordable" from a certain mindset. In the new law's Marketplace, the premium for a "benchmark" plan would cost no more than 2.5 percent of income for those now eligible for Medicaid under the ACA expansion criteria, and up to 8 percent of income (varying by age, with older buyers paying more) for those currently eligible for plans with strong CSR (that is, those with incomes up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level).

But here's the catch: The benchmark plan would have an actuarial value (AV) of just 58 percent, meaning that it would be designed to cover 58 percent of the average user's medical costs. That translates to a single-person deductible north of $6,000. By contrast, Medicaid has an AV in the high 90s, with no deductible. In the private Marketplace, CSR boosts the actuarial value of a Silver plan to 94 percent for those with incomes up to 150 percent FPL, with an average deductible of $255. For people with incomes in the 150-200 percent FPL range, CSR boosts AV to 87 percent, with an average deductible of $809, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

In sum, for 20 million people currently enrolled in health plans with deductibles ranging from $0 to $1,000 – three quarters of whom (in Medicaid) pay no premium, the BCRA will offer plans with deductibles in the $6,000-7,000 range. It's true that enrollees could theoretically select plans offering higher AV than the benchmark plan. But those plans would be prohibitively expensive for most. In the ACA Marketplace at present, fewer than 5 percent of enrollees select a plan at a level above benchmark Silver.

Back to the future with healthcare cost sharing

The BCRA really does embody conservative theory, as reflected in an ACA repeal/replace plan published in 2015 by an all-star cast of conservative healthcare scholars writing for the conservative American Enterprise Institute. At the outset, the authors look back nostalgically to a time when patients paid for proportionately more of their care:

The diminished role of the patient-consumer is evident in national statistics. As shown in figure 1, in 1960, consumer out-of-pocket spending for medical care accounted for nearly 48 percent of all spending on health in United States. By 2000, the percentage of national health expenditures paid for directly out of consumers' pockets was down to under 15 percent, and in 2010 it was just 11.6 percent. And the actuaries at the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) project out-of-pocket spending will fall to 10.2 percent of overall expenditures in 2020.

The BCRA meets and exceeds the implicit goal here, according to CBO:

People with income below 100 percent of the FPL who were not eligible for Medicaid could generally receive premium tax credits under this legislation and not under current law. However, even with the net premium of $300 shown in the illustrative examples for a person with income at 75 percent of the FPL ($11,400 in 2026), the deductible would be more than half their annual income. The net premium of a silver plan for a 40-year-old would be about 15 percent of their annual income, and the deductible would be more than one-third of their annual income. Many people in that situation would not purchase any plan, CBO and JCT estimate, although some people with assets to protect or who expect to have high use of health care would.

The high cost sharing in the BCRA is not a bug, it's a feature. The Republican bill could aptly be called the Cost Sharing Inflation Act.

Andrew Sprung is a freelance writer who blogs about politics and policy, particularly health care policy, at xpostfactoid. His articles about the rollout of the Affordable Care Act have appeared in The Atlantic and The New Republic. He is the winner of the National Institute of Health Care Management’s 2016 Digital Media Award.