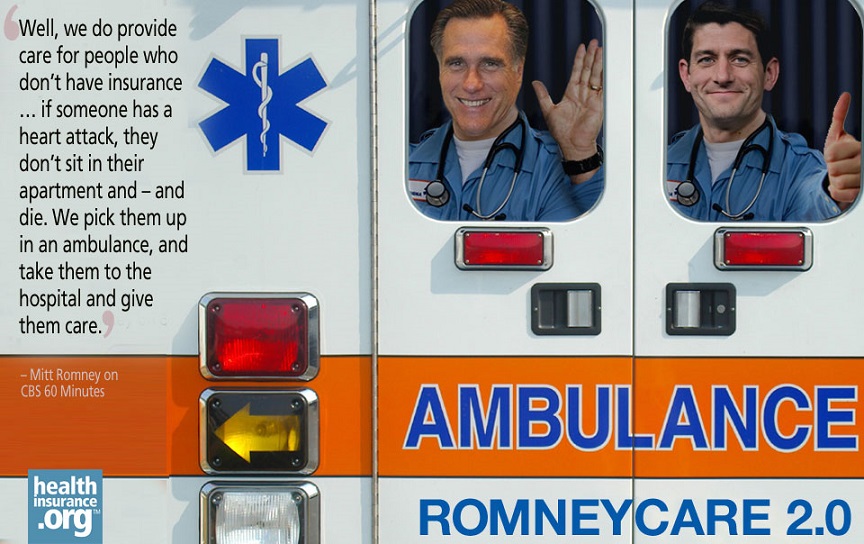

On Sunday's 60 Minutes, reporter Scott Pelley asked Governor Mitt Romney if he thinks "government has a responsibility to provide health care to the 50 million Americans who don't have it today?" Romney responded:

Well, we do provide care for people who don't have insurance ... if someone has a heart attack, they don't sit in their apartment and – and die. We pick them up in an ambulance, and take them to the hospital and give them care.

NPR's Jule Rovner asked me yesterday about Romney's comments. My response, on Morning Edition, was pretty tough. Conservatives have claimed for years that emergency care provides a suitable safety net for people who cannot or do not obtain health insurance coverage. As I described early in the health reform debate, these conservatives are wrong. My Incidental Economist colleague Aaron Carroll was even tougher. Under the title "Romney resurrects zombie idea about emergency departments," Aaron simply wrote the word "sigh," followed by a succession of links covering all-too-familiar terrain.

Yes, the hospital emergency department (ED) is required to treat your acute condition. It is not required to treat your non-urgent problem, and it's perfectly entitled to demand upfront payment for such services. Kaiser's Phil Galewitz had a nice story this February reporting that about 80,000 ED patients at the nation's largest for-profit hospital chain, "left without treatment after being told that they would have to first pay $150 because they did not have a true emergency."

Even when the emergency department is legally or morally required to treat you, it is perfectly entitled to send you a whopping bill two weeks later for. You don't have a legal right to free care, even if you receive such care at a gritty public hospital or safety net clinic. The federal EMTALA law limits the nastiest ways providers might bother you to secure payment. There's still much these creditors can do. Scholars debate precisely how many bankruptcies are precipitated by medical bills and medical debt. No one disputes that medical costs are a key factor.

Governor Romney's comments neglect two other concerns, too.

The first is obvious. ED's are well equipped to address heart attacks or broken limbs. They are not good care sites to manage serious chronic diseases. In my work, roughly eight percent of the uninsured population – four million people – has been diagnosed with serious conditions such as cancer, stroke, diabetes, or serious heart problems. I haven't seen serious alternatives to health reform that would actually serve these men and women.

The second concern is more subtle. Our emergency care system is groaning under the load of serving a large indigent population this emergency care network was not really designed to serve well. Almost all trauma centers operate at or above their maximum capacity. It's rarely profitable to provide emergency care to the uninsured and the under-insured.

EDs also face financial pressures that lead many to close their doors. Between 1998 and 2008, the number of hospital-based EDs declined while the number of ED visits increased by about 30 percent. The sharpest increase in ED visits occurred among the uninsured and those on public insurance. A sobering recent analysis by Renee Hsia, Arthur Kellermann, and Yu-Chu Shen finds that financially-stressed safety net providers serving low-income patients are among those most likely to close their doors.

Rising wait times provide one unpleasant and scary symptom of these problems. Ramon Johnson of the American College of Emergency Physicians testified to Congress: "We simply can't always get to everyone. And if we can't get to you, we can't save your life."

Such concerns go beyond notorious horror stories and anecdotes. An important recent analysis examined a nationally representative sample of 151,000 ED visits between 1997 and 2006. These authors found a steady decline in the proportion of seriously ill patients who were actually examined by a doctor within the recommended triage period. That's a harmful trend.

I should note that liberals have their own myths, too. One of the most pernicious is the idea that universal coverage can save lots of money by reducing inappropriate ED use. I see almost no evidence for such claims. When Massachusetts implemented the forerunner to health reform, trends in emergency department use seemed quite similar to those in surrounding states that hadn't implemented similar reforms. A recent analysis concluded that expanded coverage has "thus far neither increased nor decreased ED utilization."

Patients have many motivations to seek care at the ED. Improved financial access to primary care influences some of these motivations, but not others. Moreover, analyses of ED visits suggest that non-urgent visits are more medically appropriate than health policy analysts and commentators tend to think. We need policies that make our ED care system more cost-effective, more financially sustainable and better integrated into the continuum of care than such care is today. The patients will come. We have to figure out how best to treat these patients when they arrive.

As the architect of Massachusetts' earlier reforms, Romney certainly knows these realities. Yet I can almost understand why he still said what he did on 60 Minutes. The Affordable Care Act is slated to cover roughly 30 million people who would otherwise be uninsured. Romney would repeal ACA, leaving tens of millions of people uncovered. The sheer brutality of this position requires him to take refuge in bromides that the uninsured will somehow be alright.

They won't be alright. There's no getting around this simple point.

Harold Pollack is Helen Ross Professor of Social Service Administration at the University of Chicago. He has written about health policy for the Washington Post, New York Times, New Republic, The Huffington Post and many other publications. His essay, “Lessons from an Emergency Room Nightmare,” was selected for The Best American Medical Writing, 2009.