Despite the collapse of Obamacare stabilization legislation, it may still be possible to deliver at least a bit of help to unsubsidized Affordable Care Act enrollees – by fixing the glitch in the law’s formula for determining rebates that insurers with high profits or administrative expenses have to pay. The flaw, which I learned of while working for a health plan, appears to have gone unnoticed outside of the industry. It has cheated policyholders of over $700 million so far.

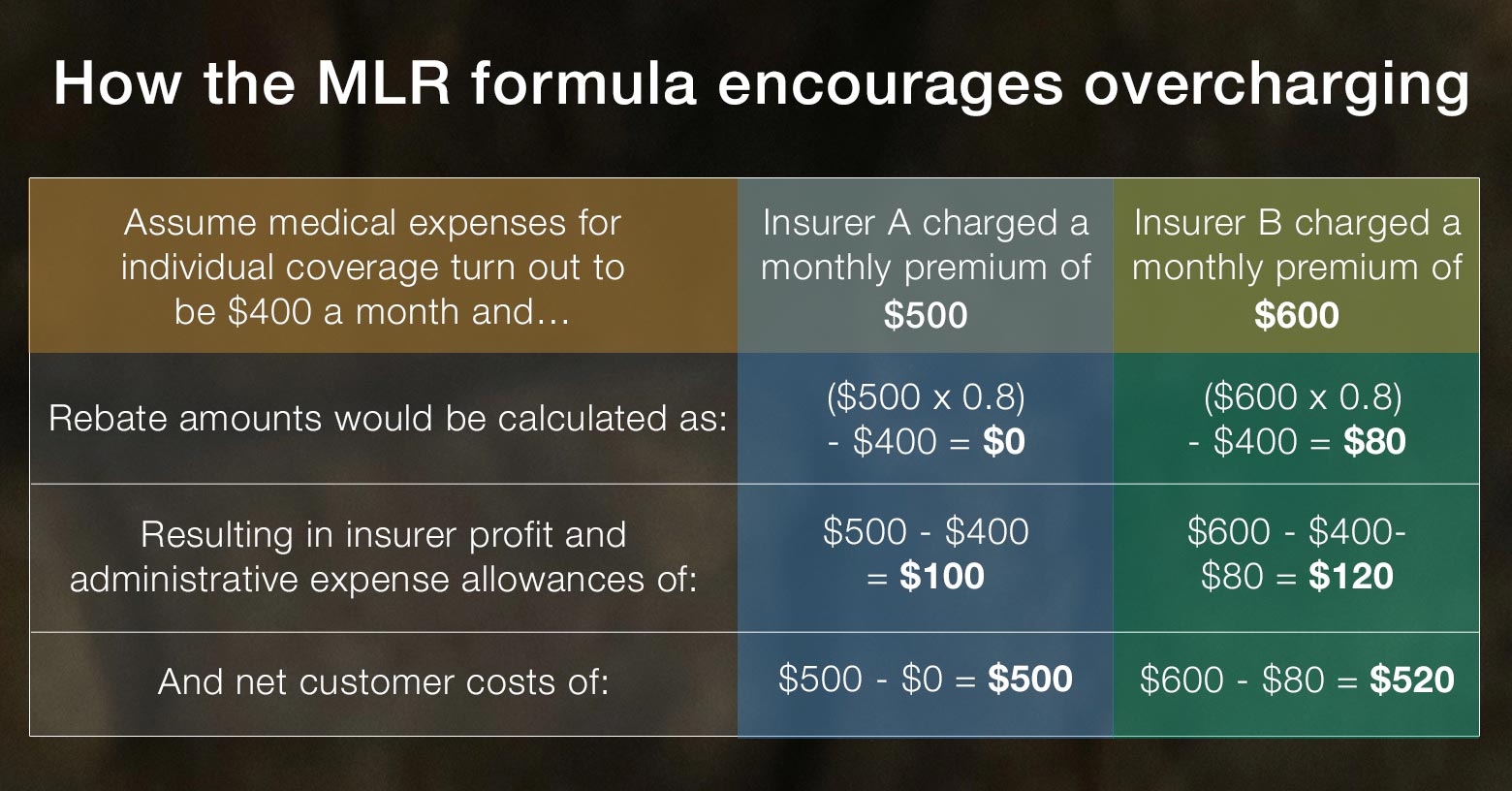

The existing formula encourages overcharging.

Under the health reform law, insurers must pay rebates whenever medical expenses account for less than 80% of premiums charged for coverage sold to individuals or small employers and 85% for coverage sold to large employers. The rebate amounts are calculated by subtracting what the insurer actually spent on medical care from 80% or 85%, as applicable, of the premiums collected.

The problem with the formula is that it enables insurers who set premiums too high and are required to pay rebates to earn higher profits than if the premiums they set meet the standard. Here’s an illustration:

For health plan customers, the bug in the formula means that if they get charged too much, the insurance company gets to keep a piece of the excess amount – 20% for individual and small group policies and 15% for large group coverage. Since the rebate provision was implemented in 2011, insurers have pocketed a total of $557 million in overcharges from individual and small group customers and $179 million from large group customers, based on total rebates paid so far.

To get the incentives right, increase rebates.

What would a fix look like? At a minimum, the incentive to overcharge should be eliminated. That could be done by adjusting the formula to boost rebates to a level that equalizes the profit and expense allowance between insurers who overcharge and those who don't. So, in the case of individual coverage, insurers who miss the 80% standard would pay rebates 25% higher than the law currently requires. (In the illustration above, $100 instead of $80.)

The better solution would be to flip the incentives and adjust the rebates so that insurers would have the same incentive to set rates meeting the standard that they currently have to overprice. If an insurer set a rate that triggered the rebate requirement, its profit and expense allowance would be reduced below what insurers who don’t overcharge are allowed – 20% lower in the case of individual and small group coverage. This would require boosting rebates to individuals and small businesses by 50%.

It would be especially helpful to consumers if the formula got fixed now since the recent repeal of the individual mandate will inject a big unknown into actuarial forecasts of enrollee medical costs for next year. When faced with that kind of uncertainty, insurers tend to price conservatively (i.e., higher), and by rewarding them for doing so, the existing rebate formula will exacerbate that problem. Adjusting the formula to instead discourage – or at least not incentivize – overpricing could make a real difference in the rates they set for next year.

Implementing a fix

Since the glitch in the formula is written into the law, fixing it would require legislation. While congressional action of any kind on Obamacare would be a heavy lift, this bit of reform might have some appeal on both sides of the aisle. It would offer Republicans a way to tamp down premium hikes that will be announced just before the November elections without adding to government spending, and would offer Democrats a way to strengthen Obamacare’s consumer protections. In addition, polling shows that majorities of both Democratic and Republican voters support the rebate provision, so giving it more teeth would likely be broadly popular.

An alternative approach might be for states to take action on their own. The Affordable Care Act allows states latitude to set stricter rebate standards than those written into the federal law. However, it is unclear whether that would include revamping the formula. That’s something lawyers will need to consider.

Fixing the rebate formula would admittedly provide only modest relief – far less than is needed. But with rates as high as they are and headed even higher, Obamacare enrollees could use all of the help they can get.

Michael Johnson is the former director of public policy at Blue Shield of California (2003 – 2015). He is currently waging a campaign to force the nonprofit health plan to provide greater community benefit.