Of all the failings in the U.S. healthcare system, among the most outrageous is the balance billing of insured patients at in-network hospitals by out-of-network doctors or other healthcare providers.

Tales abound of insured patients who did everything right, arranging for treatment by an in-network surgeon or other provider, but still ended up confronted by enormous bills – usually when out-of-network providers of ancillary services billed them for the difference between what the insurer paid and what the provider wanted to charge.

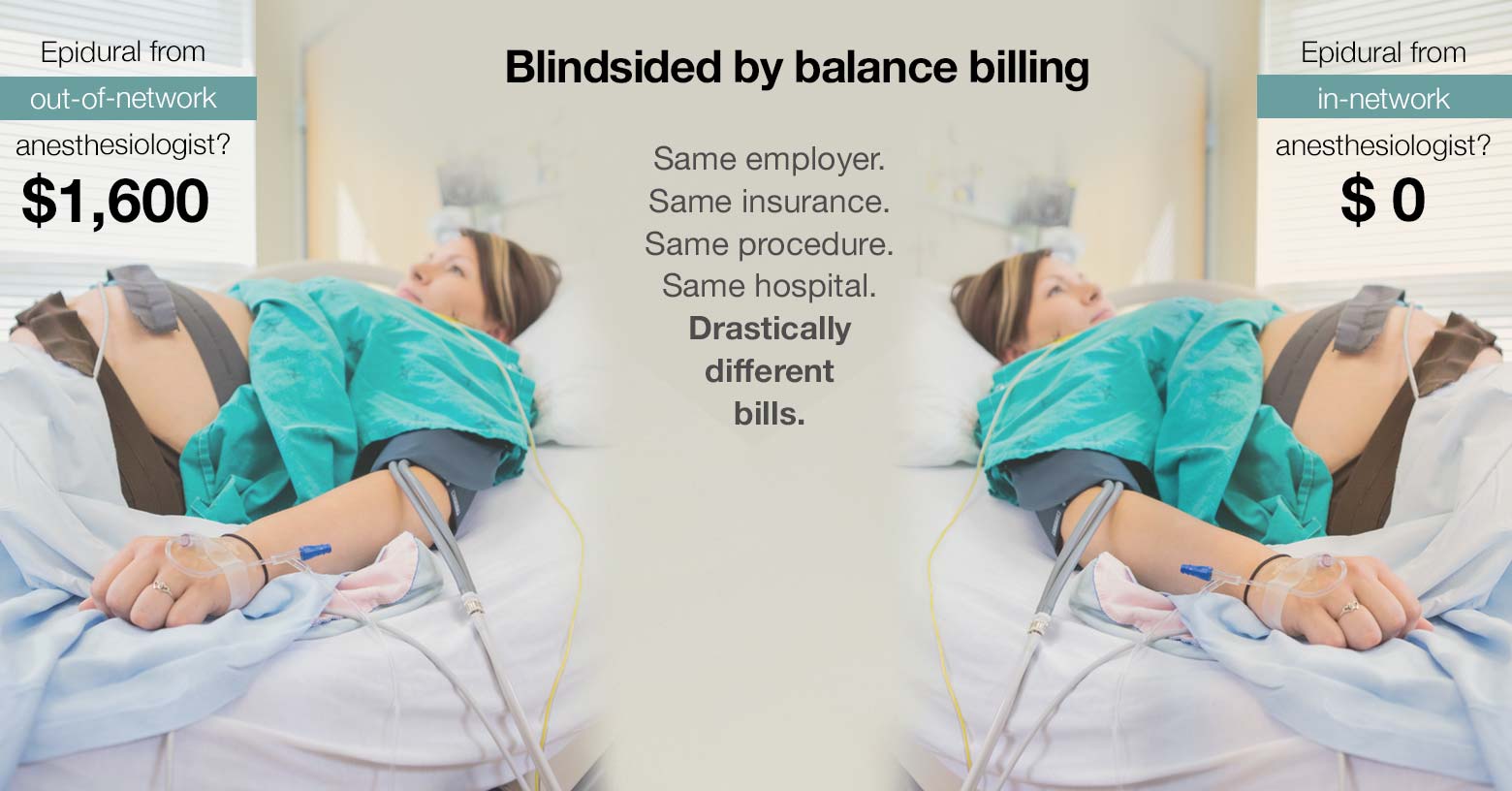

A New York Times exposé led with the case of a man who arranged with his orthopedist for neck surgery at an agreed price – and was billed $117,000 by an out-of-network assisting surgeon. Vox reported another case in which two women working for the same employer and having the same insurance gave birth within weeks of each other at the same hospital. One was billed $1,600 for an epidural by an out-of-network anesthesiologist who happened to be at work that day; the other (who also had an epidural) was billed nothing.*

Balance billing often happens after emergency care, as hospitals increasingly contract out ER staffing to outside physicians' groups. It's also a common occurrence when a patient schedules a procedure with an in-network provider – say, a surgeon – and is then balance-billed by an out-of-network anesthesiologist, or radiologist, or physical therapist, or all of the above.

Billing surprises on the rise

Balance billing has become more frequent as insurers narrow their provider networks in an effort to control costs. A Consumers Union survey conducted this past March indicated that 30 percent of privately insured Americans received a "surprise medical bill" in the past two years, with their health plan paying less than expected. In emergency care in particular, ensuring that providers are in-network is impossible. Even in a scheduled procedure, patients generally cannot control who will provide the myriad support services.

Balance-billed patients are pawns in an ongoing price war between insurers and healthcare providers. In most wealthy countries that have private health insurance, all insurers pay the same rates for the same healthcare services. In the U.S., it's every insurer for itself, and healthcare providers have been able to divide and conquer, charging prices that are often two and three times those of their counterparts in other wealthy countries.

Insurers try to gain pricing leverage by excluding from their networks doctors, hospitals and other providers who won't accept their payment rates. The result is so-called "narrow networks" – and the growing phenomenon of hospitals that are in a patient's network while large numbers of the doctors roaming the hospital's halls are not.

Insurance commissioners to the rescue?

In the U.S., insurance regulation is mainly left to the states, and only a few states provide significant protection against balance billing by out-of-network providers. Help may be on the way, though, from a source most Americans have never heard of: the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC).

While insurance is regulated state-by-state, the NAIC periodically issues model laws, designed to serve as a template for state legislatures. In late November, the NAIC unanimously approved a model act designed to ensure that health plans maintain adequate provider networks. It includes a set of protections against balance billing.

The NAIC model act permits balance billing and requires patients to be proactive, reading fine print and taking the initiative to pass the bill to their insurers. If they do so, they are largely but not completely protected.

Protection is strongest for patients who received emergency care at an in-network facility. If balance billed, all such patients need to do is forward the bill to their insurer, and their responsibility ends.

The protections for non-emergency patients – say, again, someone who schedules an operation with an in-network surgeon and is balance-billed by an attending anesthesiologist or assisting surgeon – are less complete. If the balance bill is under a certain threshold, penciled in at $500, the model rule offers no new recourse. That's true regardless of how many bills below the threshold the patient gets.

If the bill is more than $500, a required notice instructs the patient that she can forward it to her insurer, who must have a process in place for resolving it. As an opening gambit, the insurer can offer to pay the provider its in-network rate, or the rate that Medicare would pay plus a certain percentage (unspecified in the model act). If the provider does not accept that offer, the two parties either negotiate payment or go to mediation.

Among state laws providing balancing billing protections, the model act's provisions on this front appear to be closest to those of a Texas law, which also sends balance bills to mediation. It's weaker than a New York law, passed in April 2015, which essentially holds the patient harmless for any balance billing at an in-network facility – as long as the balance-billed patient fills out a form and sends it to his insurer.

A partial solution

If adopted as is, how fully will the model act protect a balanced-billed patient who exercises her option to send the bill to her insurer? "If it goes to mediation, the intention is that the patient will be held harmless," says Stephanie Mohl of the American Heart Association, who served as a consumer liaison to the NAIC and advocated for balance billing protections.

The model act does not explicitly guarantee, however, that once the insurer settles the bill with the provider, it won't hold the patient responsible for a portion larger than he would pay for in-network care. The Texas law, upon which this provision is most closely modeled, does not provide such a guarantee, according to Stacey Pogue of the Texas-based Center for Public Policy Priorities.

In practice, however, Pogue says that when patients do initiate mediation, the system seems to be "working really well." Anecdotally, she has heard (mainly from insurers) that the bill is usually resolved with a brief phone call, and insurers usually cover the whole negotiated price.

Pogue adds two caveats, however. First, the mediation option is generally buried in a balance bill's fine print, and many patients may not notice it or exercise the option. Second, if the patient's in-network obligation is a coinsurance payment – a percentage of the provider's fee rather than a fixed amount per procedure – she may be on the hook after mediation for a percentage of a higher bill.

The NAIC model act, like the Texas law, is likely to limit but not entirely end patients' exposure to balance billing for care at an in-network facility. It may also reduce the incidence of balance billing by making insurers and providers work together to resolve disputes. Pogue says that insurers tell her that "mediation in Texas is opening the door for more contracting" – that is, helping to make narrow networks less narrow. "It's an administrative hassle to mediate claims – easier to negotiate and come up with a contract," Pogue observes.

A non-partisan issue

Why not simply ban balance billing when the patient is treated at an in-network facility? Medical care providers and health insurers are powerful interests, and neither is apparently willing to forgo using patients as pawns in their eternal price wars. Doctors fear that if they can’t balance bill, insurers will feel no pressure to widen their networks. Insurers fear that if the onus is on them to settle bills in excess of their in-network rate, doctors will feel no pressure to accept those rates.

On the other hand, balance billing is such an egregious abuse of the basic concept of insurance that elected officials in both parties are under pressure to contain it. Claire McAndrew of Families USA, also a consumer liaison to the NAIC, says that balance billing "hasn't been an issue of division along party lines. Folks in every party are hearing about this from their constituents." Pogue points out that Texas' 2009 law restricting balance billing (since strengthened) was sponsored by a very conservative Republican, Kelly Hancock, and co-sponsored by a liberal Democrat, Trey Martinez Fischer.

The NAIC model act also represents a bipartisan consensus of sorts. The American Heart Association's Mohl notes that the NAIC is "a consensus-based organization" and "the expectation is that when NAIC passes a model act, a majority of states will take it up and pass it."

If the NAIC model act is widely adopted, it will not end balance billing. The onus will still be on patients to read fine print, forward their bills and make sure that they are resolved. Those who play by these rules, however, are likely to avoid all, or at least most, of their liability to balance billing out-of-network providers. And as insurers and providers are pushed to resolve their billing differences systematically, they may find it easier to agree on in-network contract terms.

*Often, patients get some relief in the most egregious cases. In the case of the neck surgery described above, the insurer ultimately agreed to pay the assistant surgeon's fee, though the patient regarded paying the full amount as ridiculous. In the case of the epidural, the insurer picked up the bulk of the charge but left the patient paying an extra $560. Such resolutions are highly unpredictable and often not available to the patient.

Andrew Sprung is a freelance writer who blogs about politics and policy, particularly health care policy, at xpostfactoid. His articles about the rollout of the Affordable Care Act have appeared in The Atlantic and The New Republic. He is the winner of the National Institute of Health Care Management’s 2016 Digital Media Award.