Watching the trench warfare over health reform, you might think liberal and conservative health wonks disagree about everything. You'd be forgiven for thinking so, but we actually agree about some basic problems – though we don't always agree about the best way to solve them.

Just about everyone from conservative Avik Roy to liberal Harold Pollack agrees that Medicaid underpays doctors and specialists. Advocates have (unsuccessfully) sued states over this, arguing that low reimbursement rates effectively deny people access to needed services. Conservatives rightly observe that some of the bluest states in the nation offer terrible Medicaid reimbursement rates. To some extent, they subsidize safety net care in other ways. To some extent, they just choose to skimp on something that is not very visible to the voting public.

Just about everyone agrees that when Medicaid underpays, it hurts safety net providers and hinders patients' efforts to obtain needed care. States wouldn't get away with such penny pinching if it affected more powerful constituencies. Sure enough, Medicare pays doctors a lot more than Medicaid does.

Academic medical centers – including my own – attract harsh criticism because they aren't always welcoming of poor people. Some of the criticism is deserved. But there's more to the story. When state Medicaid programs – including my own – pay too little and too late, it's entirely predictable that many medical practices and hospitals will drag their feet in taking Medicaid patients. That's not a liberal or a conservative statement. It's acknowledging economic reality.

Nestled in the junk DNA of the Affordable Care Act was a nice provision to address one aspect of this problem. ACA (temporarily) raised Medicaid payments to primary care doctors to the same levels paid by Medicare. On average, that represented about a 73 percent increase in such fees.

New study clearly illustrates impact

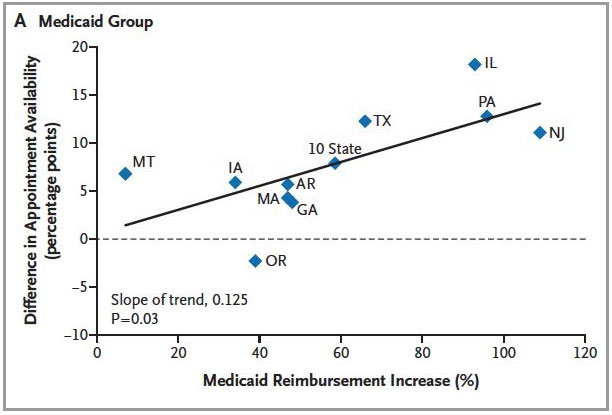

Today, the New England Journal of Medicine published a study that examined the impact of these policies. A University of Pennsylvania team led by Daniel Polsky performed an excellent "audit study" to examine the impact of higher reimbursement rates on availability of primary care appointments and patient waiting times in ten states across the country. The craftsmanship of this study, whose authors have published other important audit studies, makes this a definite addition to my health policy reading list.

As you can see, the new ACA policy greatly increased Medicaid reimbursements in several of these ten states, increasing it by a smaller amount in a others.

To simplify just a bit, research staff called a random sample of medical practices and tried to schedule appointments as new patients. Sometimes the researchers called to schedule a routine checkup. Sometimes they mentioned more urgent concerns ("I think I might have high blood pressure.") The callers would also identify what kind of insurance they carried: sometimes Medicaid, sometimes private coverage.

I'll let you guess what the researchers found ...

Right!

Callers were less likely to get appointments when they said they had Medicaid. Amazingly enough, the differences between the two groups were most dramatic in states that began with the lowest Medicaid fees, where the new ACA policy had the biggest impact.

Increased rates, increased provider availability

When reimbursement rates were increased by the ACA, Medicaid recipients were about 8 percentage points more likely to successfully schedule an appointment (58.7 percent success before the increase versus 66.4 percent with higher reimbursement).

These aren't miracle findings, of course. I should also add that audit studies have inherent limitations. Such studies do not show that Medicaid patients can't find doctors. (If one randomly audited country clubs 50 years ago, naïve researchers might have inferred that Jews and African Americans lacked any way to play golf. In fact, minority golfers learned where they could play on other, segregated courses.)

Aaron Carroll rightly observes that Medicaid gets a bit of a bad rap. It actually compares favorably on consumer satisfaction measures to private insurance – particularly to non-fancy policies often sold to low-income people. Audit studies often compare Medicaid to brand-name private coverage.

Still, there's no doubt that Medicaid's low provider payment is a serious problem. This channels Medicaid patients into safety net providers and academic medical centers that either must eat a financial loss or are able to recoup these apparent losses in other ways. That's not a great way to operate an equitable health system.

So ACA implemented a small but worthy effort that benefited both Medicaid recipients and rather hard-pressed primary care providers. As of last June, the federal government has spent about $5.6 billion on this effort. That money appears to have been well spent. Here's something both parties should agree on – pay Medicaid providers on a more level playing field with private insurance and Medicare.

Except for one thing ... Neither party cares quite enough about this issue to make it happen.

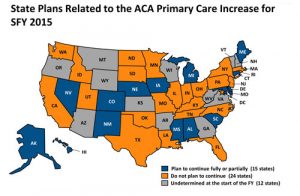

15 states show support for increased rates

For reasons that baffle me, ACA made Medicaid's enhanced reimbursement temporary. It expired December 31. Fifteen states plan to use their own money to continue the effort. Interestingly enough, some of these states (Mississippi, Alabama, and South Carolina) are quite conservative on other matters of health policy. In many other states, Medicaid primary care providers just took a major hit.

Some liberal senators have proposed extending the subsidy another two years. You can guess how likely that is to pass. Republicans commentators frequently and specifically criticize Medicaid for its low reimbursement. Republican lawmakers seem conspicuously scarce when it comes time to put cash on the table to actually address this problem.

$5.6 billion seems like a lot. It's actually a pittance when one considers that this effort requires less than one percent of Medicaid's $450+ billion annual budget.

In a sane world, Congress and the Obama administration would examine this study, celebrate another small but successful component of health reform, and find a way to continue it. In the world we live in, that's not going to happen.

Harold Pollack is the Helen Ross Professor at the School of Social Service Administration. He is also Co-Director of The University of Chicago Crime Lab. He has published widely at the interface between poverty policy and public health. Pollack serves as a Fellow at the MacLean Center for Clinical Ethics at the University of Chicago, and as an Adjunct Fellow at the Century Foundation.