Most mornings, I walk through the Pedway to the University of Chicago Urban Labs. If you know Chicago, the Pedway is an underground concourse that runs due west about a mile from Millennium Station all the way to City Hall.

The Pedway houses my favorite Dunkin's and other fine cuisine. It also houses conspicuous numbers of men and women who are homeless. Just this morning, I rushed past a man curled on the floor holding his possessions, trying to stay warm. His dirty clothes were too thin for a tough Chicago winter. I doubt he has showered in days. Hundreds of busy commuters looked over, then looked past, as we walked on by. Big-city life makes us callous to everyday calamities we see before us. There's really no way to avoid it. You occasionally hand over some pocket change or a dollar. There's too much misery to engage everyone who desperately needs help.

The homeless you see – and more out of sight

An estimated 550,000 Americans are homeless on any given night; 1.4 million will spend at least some time in a shelter this year. These figures, bad as they are, understate the problem. The street and shelter homeless are merely the most visible group of our fellow citizens who lack stable housing. Millions of others are precariously housed, couch-surfing with friends and relatives. Others are one missed paycheck away from losing an apartment or a home. I'm not counting people who would have no place else to sleep if they were suddenly released from jails, prisons, and other institutional settings.

There's no magic cure for homelessness or its sibling, extreme poverty. Both Blue states and Red states have made bone-headed mistakes that make these problems worse than they would otherwise be. Wealthy coastal states hinder development of affordable housing for people who need it the most. When I travel on business to San Francisco, I meet cabbies whose monthly rents on small apartments frequently exceed the mortgage payment on my four-bedroom house.

Red states mostly avoid that blunder. But the deepest Red areas make an even bigger one, hurting millions of people out of partisan spite by spurning Medicaid expansion. This leaves almost 3 million people vulnerable to medical bills, 90 percent in southern states, leaving safety net providers and rural hospitals holding the bag for uncompensated care.

Medicaid expansion is particularly important given the large proportion of homeless men and women who experience physical health challenges, psychiatric disorders, and substance use disorders, and who require Medicaid coverage to receive proper care.

Health issues: a symptom driving homelessness

Most adults who meet the definition of street or shelter homelessness have some history of serious mental illness, alcohol, or illicit drug use disorders. Rates are even higher among people who are homeless and require medical care. These disorders drive homelessness for many reasons – not least because these easily fray bonds with people close to you whom you might turn to for help. And the major and minor traumas of being homeless – among which I'd include watching comfortable coffee-drinking commuters like Harold Pollack walk past in your hour of need – aren't great as you seek to manage whatever mental health challenges you may have.

Others who are homeless or precariously housed live with physical ailments that are scarcely less debilitating or dangerous. It's hard to manage your hypertension or diabetes when you're living out in the street. Untended and exposed to the elements, minor scratches and blisters easily become infected open sores. Three-quarters of people who are homeless smoke tobacco, with all-too-predictable consequences for their health and longevity.

If you regard Medicaid as the safety-net for the most vulnerable, you might have assumed that at least health coverage for the homeless was addressed even before the Affordable Care Act. Not so, not even in the most liberal states.

Low (or zero) income by itself does not qualify people for traditional Medicaid. Even when people experience physical or mental health disabilities that do entitle them to receive Medicaid, the bureaucratic process for is lengthy and daunting. People who are homeless can't always produce the neat manila folders filled with the medical records, raised-seal birth certificates, and other documents required for the complicated paperwork, either. Since 1997, addiction has been specifically barred as a qualifying condition for federal disability programs that bring Medicaid eligibility.

How Medicaid expansion can impact the homeless ...

For all of these reasons, fewer than 20 percent of homeless Californians were on Medicaid before the Affordable Care Act was passed. So the impact of Medicaid expansion for homeless people was almost immediate. Michael R. Cousineau describes innovative measures in many cities which used Medicaid funds to improve supportive housing and mental health services out in the community to serve men and women who otherwise avoid the mental heath system.

The experience of Baltimore nonprofit, Healthcare for the Homeless, exemplifies the pattern seen in many expansion states. Before ACA, only 30 percent of their patients were insured. Now, 90 percent are insured. Comparisons across states around ACA's passage demonstrated much sharper coverage increases among the homeless in Medicaid expansion states. Moreover, homeless services providers used the resources available through Medicaid expansion to expand services, increase outreach, and to take other steps that improve care for people who live in shelters or the street, or who are in danger of losing a place to live.

... and millions on the verge of becoming homeless

Medicaid expansion probably matters even more to prevent people from becoming homelessness in the first place. An estimated 13.6 percent of those made newly eligible for Medicaid have been diagnosed with a current substance use disorder. An estimated 5.4 percent carry diagnoses of serious mental illness. Many more have some history of mental illness or addiction, or face less-severe mental health, alcohol, or drug-use-related challenges that merit appropriate intervention. These challenges are particularly acute surrounding the opioid epidemic – which is one reason why Ohio Gov. John Kasich and other Republican leaders in Red-leaning states have been important allies in the fight to expand Medicaid.

Medicaid expansion has helped states to provide better services for people who experience mental health and addiction disorders. A team led by Colleen Grogan, Amanda Abraham, Christina Andrews, Pete Friedmann, Cliff Bersamira (and one other guy) documents that addiction treatment is more expansive and more available in Medicaid expansion states. More services are covered. Waiting lines are shorter. Fewer people are turned away because they cannot pay.

Reduced healthcare debt can mean fewer evictions

Medicaid expansion also prevents homelessness in another way. Insurance and medical care are very expensive. So are private insurance deductibles and copays that are essentially absent from Medicaid. Medicaid protects people against severe financial hardships, and puts more money in the pockets of poor people who desperately need the help. Results from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment (OHIE) and other studies demonstrate that Medicaid coverage significantly improved participants' self-reported health status, and reduced the incidence of depression. In no small part, these benefits are linked to reducing stress and anxiety associated with unpaid bills.

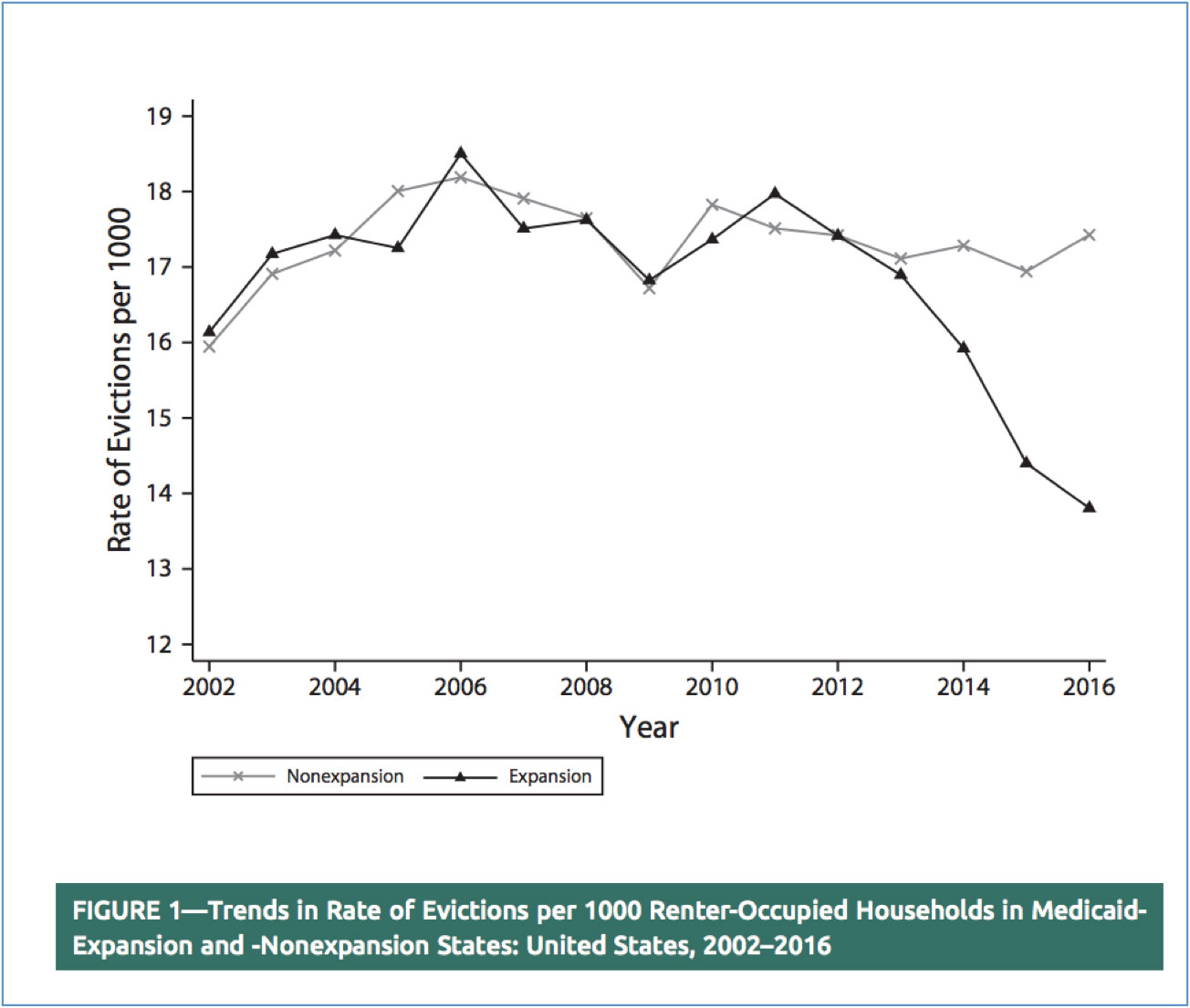

Source: Zewde, et al. American Journal of Public Health, October 2019, p. 1381.

As the OHIE authors reported, Medicaid coverage "reduced medical debts sent to collection agencies, lowered the likelihood of borrowing money or skipping other bill payments to cover medical expenses, and virtually eliminated catastrophic out-of pocket medical expenditures."

A Columbia University team led by Naomi Zewde recently compared patterns of rental housing evictions between expansion and non-expansion states. Given the financial realities of Medicaid, it's perhaps unsurprising that Medicaid expansion was associated with a significant reduction in the rate of apartment renters evicted from their homes.

The authors provided a suitably professional statistical analysis. Their basic finding is clear in the simple graph shown above. Comparing the black and gray lines, one sees that eviction rates were broadly similar in expansion and non-expansion states before ACA was passed in 2010. Then the lines diverge. By 2016, evictions were notably less common in the expansion group.

No. Medicaid is not a miracle cure for homelessness.

I see every day in the Pedway that Medicaid expansion is no miracle cure for homelessness. But it helps.

Finding things that help. That's the core mission of much of my work, and the work of my colleagues, too. It’s naïve to think that any single policy or intervention is the polio vaccine that ends homelessness, poverty, opioid addiction, or other daunting challenges. But we have reasons for realistic evidence-based optimism that feasible policies such as Medicaid expansion can be fielded at a large enough scale to matter, and that these genuinely help.

It's easy to lose that optimism. It's tempting to remain sad about daunting problems. We drop a few bucks into a Salvation Army bucket, but become pessimistic and therefore passive that much can be done that can really make a difference.

We can't succumb to that temptation. Together, we all can protect each other from homelessness and other calamities that would crush any one of us, if we had to face it alone. People at risk of becoming homeless – everyone in America – deserves the basic protections Medicaid provides. This is not a partisan issue but a human one. This holiday season, it's good to remember that we owe at least that to our fellow citizens.