Medicaid eligibility and enrollment in Arkansas

Proposed state plan would move expansion enrollees from QHPs to fee-for-service Medicaid if they fail to participate in life/economic improvement program

Who is eligible for Arkansas Medicaid?

The federal government specifies certain low-income populations (for example, pregnant women) that must be covered in order for a state to qualify for Medicaid funding. The federal government also defines optional coverage groups and establishes baseline income guidelines. States can set eligibility limits at or above the federal guidelines.

Here is where Arkansas has set its eligibility levels (including a built-in 5% income disregard for children, pregnant women, and non-elderly adults):

- Children from birth to age 18 with incomes up to 216% of FPL (that’s for CHIP; the limits for Medicaid eligibility are lower)

- Pregnant women with incomes up to 214% of FPL (coverage for the mother still only lasts for 60 days after the birth; the majority of the states have extended this to 12 months, but Arkansas has not. Legislation that would make this change — HB1010 — failed to advance in the Arkansas legislature in 2023)

- Non-elderly adults with incomes up to 138%

- Certain elderly and disabled individuals (both income and asset limits apply to these populations).

for 2026 coverage

0.0%

of Federal Poverty Level

Apply for Medicaid in Arkansas

You can enroll in Medicaid online at Access Arkansas. Or you can visit a Department of Human Services office in your county, or call 1-800-482-8988.

Eligibility: Children from 0-18 with incomes up to 211% of FPL; pregnant women with incomes up to 209% of FPL; parents with incomes up to 138% of FPL; non-elderly adults with household incomes up to 138% of FPL; certain elderly and disabled individuals.

ACA’s Medicaid eligibility expansion in Arkansas

Arkansas expanded Medicaid under the ACA starting January 1, 2014. But the state took a unique approach — guided by legislation enacted in 2013 and a subsequent federal waiver approval — that involves purchasing private qualified health plans (QHPs) through the exchange/marketplace for Medicaid expansion enrollees. (This is why the total number of QHP enrollees in Arkansas is so much higher than the number of exchange enrollees reported by CMS; the Medicaid enrollees have QHPs but are not technically counted as exchange enrollees.)

The Medicaid expansion program in Arkansas is currently known as ARHOME (Arkansas Health and Opportunities for Me). As of January 2023, there were 342,267 people enrolled in ARHOME, amounting to about 30% of the state’s total Medicaid population. By September 2023, enrollment in ARHOME had dropped to 239,990 people, due to the disenrollments during the unwinding of the pandemic-era continuous coverage rule. Total enrollment in Arkansas Medicaid had dropped to under 900,000 people by that point.

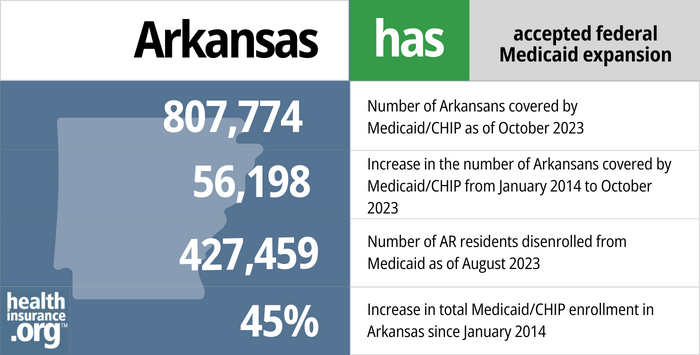

- 807,774 – Number of Arkansans covered by Medicaid/CHIP as of October 20231

- 56,198 – Increase in the number of Arkansans covered by Medicaid/CHIP from fall 2013 to October 20232

- 427,459 – Number of AR residents disenrolled from Medicaid during “unwinding” of continuous coverage rule3

- 45% – Increase in total Medicaid/CHIP enrollment in Arkansas since fall 20132

Explore our other comprehensive guides to coverage in Arkansas

Arkansas residents enroll in ACA-compliant plans through a state-based exchange that utilizes the federal enrollment platform (SBE-FP).

In 2023, there are three insurers that offer stand-alone individual/family dental coverage through the health insurance marketplace in Arkansas.4 Learn about the various dental coverage options in our state guide.

There are nearly 670,000 Medicare beneficiaries in Arkansas as of 2023.5 Read our overview of Medicare enrollment and coverage options in Arkansas.

Arkansas residents can buy short-term health insurance plans with initial durations up to 364 days. And as of 2023, at least nine insurers sell short-term plans in the state.6

Frequently asked questions about Arkansas Medicaid eligibility and enrollment

How do I enroll in Arkansas Medicaid?

You can enroll in Medicaid online at Access Arkansas. Or you can visit a Department of Human Services office in your county, or call 1-800-482-8988.

You can also begin the process online through Healthcare.gov if you are a non-disabled adult under age 65. If you’re found to likely be eligible for Medicaid, the system will direct you to Access Arkansas.

How did Arkansas handle Medicaid renewals after the pandemic?

During the COVID pandemic, states received additional federal Medicaid funding, but were also prohibited from disenrolling anyone from Medicaid. That rule ended on March 31, 2023, so states could resume disenrollments as of April 1, 2023, terminating coverage for people who are no longer eligible for Medicaid.

States have 12 months to initiate eligibility redeterminations for everyone who was enrolled in Medicaid as of March 2023. However, Arkansas only took six months to complete eligibility redeterminations for everyone whose coverage had been extended during the pandemic (i.e. their eligibility hadn’t been confirmed within the past year).7 During that time, a total of 427,459 people were disenrolled from Arkansas Medicaid.3

Under federal rules, states could start the process of redetermining eligibility in February, March, or April 2023 (disenrollments couldn’t come before April 1), and Arkansas opted to begin as soon as possible, in February 2023. And by October, eligibility redeterminations had been completed for everyone whose coverage had been extended without an eligibility verification during the pandemic.

Arkansas enacted legislation (SB295/Act 780) in 2021 that required the state to conduct eligibility redeterminations within six months of the end of the continuous coverage period, for any Medicaid enrollees whose eligibility had not been redetermined within the prior 12 months. The federal government implemented a variety of consumer protection guardrails for the “unwinding” of the continuous coverage period, and recommended that states not initiate more than one-ninth of their eligibility redeterminations in any given month.

In their comprehensive unwinding plan, Arkansas noted that the state is “mindful of CMS’s concerns about initiating renewals for no more than 1/9 of total caseload in any given month. Renewals for groups that need to be handled over several months to accommodate the caseload recommendation will be distributed based on original renewal date.”

The CMS recommendation is based on a state’s total caseload, and not initiating renewals for more than 1/9 of them in any given month. The Arkansas approach of completing redeterminations in six months was only applicable to people whose eligibility had not been redetermined within the last year. That’s not their total caseload, since many of their enrollees would have had their eligibility determined within the last year, including new enrollees, ex parte — automatic — renewals, and people who did complete renewal paperwork during the pandemic and continued to be eligible.

Now that eligibility redeterminations have been completed for the population whose coverage was extended during the pandemic, Arkansas has returned to the normal protocol of conducting eligibility redeterminations for all enrollees once per year. In other words, a person who enrolled in Arkansas Medicaid in early 2023 would not have been among the population whose eligibility had to be rechecked in the first six months of the “unwinding” period. Instead, their eligibility will be redetermined in late 2023 or early 2024, in advance of the anniversary of their enrollment.

In February 2023, Arkansas published a detailed overview of how the unwinding process would work in the state. They noted that there were roughly 422,000 enrollees (out of more than 1.1 million total enrollees) whose coverage has been extended during the pandemic but who either no longer met the eligibility criteria or had not responded to renewal notices that were sent out during the pandemic. Eligibility redeterminations were prioritized for these enrollees.

People who lost Medicaid in Arkansas could transition to other available coverage. Most employer-sponsored health plans have 60-day enrollment windows due to loss of Medicaid; if you miss that window, you’d have to wait until your employer’s next open enrollment period. For people who are eligible for Medicare, the federal government is offering a special enrollment window during which a person can transition from Medicaid to Medicare without a late enrollment penalty; it continues for six months after the Medicaid termination date.

And for people who need to obtain their own coverage (ie, they aren’t eligible for Medicare or an employer’s plan), HealthCare.gov is offering a one-time 16-month special enrollment period for people who lose Medicaid anytime between March 31, 2023 and July 31, 2024. This is important, as the enrollment window for individual/family coverage due to loss of other coverage normally only continues for 60 days after the coverage loss, but the rules have been adjusted to help people who are impacted by the “unwinding” of the pandemic-related Medicaid continuous coverage rules.

What is Arkansas' Medicaid expansion 'private option'?

Arkansas is among the states where Medicaid expansion has been implemented, but the state uses a non-standard approach via a waiver. Arkansas’ Medicaid expansion waiver (current version here) allows the state to use Medicaid funds to cover the cost of securing private qualified health insurance plans (QHP, through the Marketplace/exchange) instead of using a fee-for-service or Medicaid managed care approach.[/hio_question]

Arkansas briefly implemented a work requirement for the Medicaid expansion population in 2018, but it was soon overturned by a judge after thousands of people lost coverage (details below). In 2023, Arkansas submitted a waiver amendment to CMS (still pending as of early 2024) seeking to implement a new approach.8

Under the proposed amendment, enrollees would have access to coaching/job training and assistance with obtaining a job. If an enrollee “consistently declines to participate in health improvement and economic independence opportunities,” they would be moved out of their QHP and reassigned to fee-for-service (FFS) Medicaid. Nobody would lose coverage or receive fewer benefits under the new proposal, but the state does make it clear that they consider the overall experience in a QHP to be superior to FFS Medicaid.9

Arkansas initially referred to its Medicaid expansion as the Private Option (officially the Arkansas Health Care Independence Program). They later changed the name of the program to Arkansas Works, and then to Arkansas Health and Opportunities for Me, or ARHOME. But the state still purchases private plans for enrollees, using Medicaid funds. Enrollees can pick from among certain silver plans in their area, and Arkansas Medicaid pays the premiums. For those who don’t select their own plan, there’s an auto-enrollment protocol that seeks to spread enrollees across the participating QHPs in the area.

Arkansas paused automatic enrollment in private plans for new enrollees in late 2022, although they still had the option to select a private plan. As of 2022, about 90% of ARHOME enrollees were in private plans and 10% were in traditional Medicaid; the state is targeting an 80/20 split instead. Their protocol for 2023 noted that the 80/20 split will continue to be used, and that auto-enrollment in QHPs will be paused anytime the 80% threshold is exceeded.

The state’s privatized approach to Medicaid expansion has been considered by a number of other states, but also faces criticism for being less cost-effective than regular Medicaid expansion. New Hampshire implemented a similar program, although they transitioned to Medicaid Managed care instead as of 2019 and Iowa also started out with a privatized approach, but transitioned to regular Medicaid managed care in 2016.

As of 2023, Arkansas is the only state still utilizing a private option approach (ie, with Medicaid expansion enrollees covered under state-purchased QHPs in the exchange, instead of fee-for-service or managed care Medicaid coverage).

Legislation impacting Arkansas Medicaid

Arkansas Health and Opportunity for Me (ARHOME) has replaced Arkansas Works; premiums not allowed after 2022

The Arkansas Works waiver was valid through the end of 2021. As of 2022, the state switched to the Arkansas Health and Opportunity for Me (ARHOME) waiver demonstration. The 1115 waiver was approved by the federal government in December 2021, and allows the state to continue to provide private coverage (obtained via the Arkansas health insurance marketplace) to more than 300,000 people who are enrolled in the Arkansas Medicaid expansion program.

However, the waiver approval notes that after the end of 2022, Arkansas is no longer allowed to charge premiums to enrollees with income above the poverty level. Medicaid expansion covers adults with income up to 138% of the poverty level, and the Arkansas Works waiver, approved by the Obama administration, included a provision that allows the state to charge premiums (2% of income) for Medicaid expansion enrollees with income between 100% and 138% of the poverty level. But the December 2021 approval of the ARHOME waiver notes that “CMS has since determined that premiums can present a barrier to coverage, and therefore, charging beneficiaries premiums beyond those specifically permitted under the Medicaid statute are not likely to promote the objectives of Medicaid.”

Arkansas Medicaid enrollment numbers over time

Although Medicaid expansion resulted in a significant increase in enrollment in the first few years, enrollment had stabilized by 2016. Total enrollment (including expanded coverage and traditional Medicaid) as of January 2017 stood at more than a million people, but had dropped to 931,000 by January 2018. The state attributed the decrease in enrollment to a stronger economy and the state’s review of enrollees’ eligibility.

By January 2019, Arkansas Medicaid enrollment had dropped to under 850,000 people, due in part to the state’s implementation of a Medicaid work requirement in mid-2018. As of October 2018, there were 252,642 people covered under expanded Medicaid in Arkansas (i.e., they wouldn’t have been eligible for Medicaid if the state hadn’t expanded the program under the ACA). In July 2018, before people began to be cut from the program due to the work requirement, there were more than 270,000 Arkansas Works enrollees.

But in the second half of 2018, over 18,000 people in Arkansas lost their health coverage as a result of the work requirement (that doesn’t mean they weren’t working; some people were simply unaware of the reporting requirements or unable to navigate the system for reporting their work hours).

Enrollment in Arkansas Medicaid rebounded significantly during the COVID pandemic. By mid-2022, total Medicaid/CHIP enrollment in Arkansas had once again surpassed a million people, and stood at more than 1.1 million people as of early 2023, including more than 342,000 enrolled in Medicaid expansion (ARHOME).

But by the fall of 2023, after eligibility redeterminations had been completed for everyone whose coverage had been extended during the pandemic, total enrollment had dropped to 877,544, and ARHOME enrollment had dropped to under 240,000 people.

Does Arkansas have a Medicaid work requirement?

Arkansas implemented a Medicaid work requirement in 2018, described below in detail. But Federal Judge James Boasberg overturned the Medicaid work requirements in Kentucky and Arkansas as of March 2019, noting that officials had not taken steps to prevent coverage losses stemming from the work requirement.

The Biden administration officially withdrew the state’s Medicaid work requirement waiver approval in March 2021, although it had not been in effect for two years prior to that. And the state’s new ARHOME waiver, which was approved in December 2021 to continue to state’s approach to Medicaid expansion, did not include a proposal for a work requirement, as the Biden administration had made it clear that such proposals would not be approved.

So Arkansas is no longer removing people from the Medicaid program for failure to comply with the work requirement or reporting requirement, and the people who had already lost their coverage under the work requirement rules were able to re-apply for Medicaid — although many may not be aware that their access to Medicaid has been reinstated (albeit not automatically, as they do still need to re-apply for coverage).

Lawsuit over Arkansas Medicaid work requirement was slated for SCOTUS but hearing was canceled and work requirement waiver was then rescinded by HHS

After Judge Boasberg overturned the work requirement in Arkansas, the Trump administration appealed the case. A panel of three judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals for DC heard oral arguments in the appeal in October 2019. During the arguments, all three judges expressed concerns about the coverage losses that stem from Medicaid work requirements, which was the crux of Boasberg’s ruling earlier in the year that suspended the work requirement. And in February 2020, the three-judge panel unanimously ruled that it was “arbitrary and capricious” for HHS to approve the Arkansas Works waiver, and upheld Boasberg’s ruling to overturn the state’s Medicaid work requirement. (So the work requirement continued to be suspended until the Biden administration officially revoked its approval in 2021.)

In July 2020, however, the Trump administration asked the Supreme Court to intervene and allow Arkansas to reinstate its work requirement once the COVID-19 situation improved enough to allow the unemployment rate to return to normal levels. The Supreme Court justices agreed to hear the case, and oral arguments in the lawsuit, Arkansas v. Gresham, were scheduled for March 29, 2021 at the Supreme Court. (Kentucky had initially been part of the appeal, as that state’s work requirement had also been overturned, but Gov. Beshear removed Kentucky from the lawsuit and rescinded Kentucky’s Medicaid work requirement soon after taking office.)

But the Biden administration does not support Medicaid work requirements, and asked the Supreme Court to cancel the hearing. That request was granted, and Arkansas v. Gresham was not heard by the Supreme Court.

Soon thereafter, in March 2021, HHS officially withdrew approval for the Medicaid work requirement in Arkansas.

As of early 2020, Medicaid work requirements were in effect in Utah and Michigan, but both were soon paused (Michigan’s was overturned by a judge, and Utah’s was suspended as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic). The Biden administration notified states with previously approved Medicaid work requirements that they were being reconsidered, and withdrew all of them in 2021. Georgia implemented a work requirement in mid-2022, along with a modified version of Medicaid expansion (just to the poverty level, for people who comply with the work requirement).

Work requirement took effect in June 2018, and 18,000 people had lost coverage by the end of 2018

Arkansas received federal approval in March 2018 to make some modifications to the state’s Medicaid expansion program, including the implementation of a work requirement and the unconditional elimination of Medicaid’s three-month retroactive eligibility, replacing it with a 30-day retroactive eligibility provision instead. The waiver amendment was submitted in June 2017, and Arkansas had hoped to implement the changes by January 2018. But the waiver approval noted that the work requirement could be implemented no earlier than June 1, 2018.

The state wasted no time, however, and implemented it as of June 5, 2018. The work requirement was delayed until 2019 for people under the age of 30, but applied as of June 5 to people between the ages of 30 and 49 who weren’t otherwise exempt. They had to work or participate in other community engagement activities at least 80 hours per month in order to maintain access to Medicaid coverage. After three months of non-compliance, Medicaid eligibility would terminate.

So people began losing coverage as of the end of August for failure to comply with the work requirement — including failure to comply with the onerous reporting requirements, detailed below. By the end of 2018, more than 18,000 people had lost their Medicaid coverage in Arkansas under the new work requirement. A beneficiary who lost coverage due to non-compliance with the work requirement was locked out of Arkansas Works until the end of the year.

In July 2018, the state reported that 43,794 people were subject to the work requirement, which amounted to about 16% of the total Arkansas Medicaid expansion population (and less than 5% of the state’s total Medicaid population). And of the people who were subject to the work requirement, about two-thirds — more than 30,000 enrollees — were exempt from the reporting requirements based on information the state already had in its database.

The details of the state’s Medicaid waiver are described below. Of particular importance was the low-cost, high-tech approach that the state opted to take in terms of administering the work requirement. People subject to the Medicaid work requirement had to document their work hours via an online portal that the state created, and there were no alternative ways for people to submit proof that they were complying with the work requirement. I tried clicking on the “report work activities” link (no longer available now that a federal judge has shut down the state’s Medicaid work requirement) and ended up with a blank screen as of mid-June 2018; when I tried again in mid-August, the link worked correctly, but at that point, the website would shut down at 9 pm each night, and wasn’t available again until 7 am.

This is despite the fact that only Mississippi has a larger percentage of residents without access to home internet than Arkansas. The state clarified in May 2018 that people who didn’t have a computer or who had difficulty reading or using the internet would be able to designate an assister who will be able to help them comply with the verification of the work requirement, but that only serves to highlight how much of an obstacle the reporting requirements may have been for some people.

The state noted that not only was it cheaper to use an online system (versus hiring more people to work in county offices in order to have an in-person verification system), it would also encourage people to become more computer literate. But it’s important to keep in mind that Medicaid is a health care program — not a jobs program or a life skills program or a computer literacy program. And taking away a person’s health care isn’t likely to improve their situation in life.

Amid an outpouring of criticism, Arkansas added a telephone hotline in December 2018 that Arkansas Works members could use (from 7am to 9pm) to report their work hours.

By August 2018, in the third month of the work requirement implementation, the vast majority of the people who had been expected to log into the state system to report their work activity were not doing so (83% in July, and 72% in June did not report their work or exemption). Of the 13,566 people who needed to report their work hours or seek an exemption for July (based on 43,796 being subject to the work requirement but 30,228 being automatically exempt), only 844 had satisfied the reporting requirement, and 1,571 reported an exemption (the report doesn’t clarify whether all of those exemptions requests were valid and granted). The large majority — 12,722 enrollees — did not meet the reporting/exemption requirements.

Not much had changed by October. At that point, after thousands of people had already lost their coverage due to non-compliance with the work requirement (and/or simply not being able to navigate the reporting system), more than 12,000 enrollees had not reported their work to the state. Only about 1,500 had satisfied the reporting requirement, and another 1,600 had reported an exemption.

After three months of non-compliance, enrollees were locked out of the Medicaid program and ineligible for coverage until January 2019 — even if they were working and reporting their work activities throughout the rest of 2019. Many of these individuals may have been working, attending school, or otherwise complying with the work requirement in June and July, but were unaware of the reporting requirement or unable to complete the reporting due to lack of internet access and/or an understanding of how the process works.

It was also notable that very few people were “incentivized” to begin working and reporting it to the state as a result of the Medicaid work requirement. As of December, just 1,311 people reported work activity to the state, but for most of them, it was automated by meeting the SNAP work requirements. As Joan Alker, of Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute, reported, “this leaves just 462 people out of the 60,680 subject to the work requirement newly reporting work or job search activities” in December.

The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) sent a letter to HHS in early November, expressing concerns about the low level of reporting compliance in Arkansas and the high number of people who had lost their coverage. The letter notes that “the low level of reporting is a strong warning signal that the current process may not be structured in a way that provides individuals an opportunity to succeed, with high stakes for beneficiaries who fail.” MACPAC has called for a pause in disenrollments until adjustments are made “to promote awareness, reporting, and compliance.”

As noted above, the Medicaid work requirement in Arkansas was halted in March 2019 when Federal Judge James Boasberg ruled that the approval HHS had granted to Arkansas to implement a Medicaid work requirement “cannot stand” and was vacated. Although a legal battle ensued for the duration of the Trump administration, the Biden administration officially withdrew federal approval for the state’s Medicaid work requirement waiver in 2021, putting an end to the case.

Transition to Arkansas Works in 2017

In April 2016, lawmakers in Arkansas voted to approve and fund an overhaul of Medicaid expansion in Arkansas, dubbed “Arkansas Works.” The state submitted the new waiver proposal to CMS in June 2016, and CMS reviewed it over the following months. In December 2016, CMS granted approval for most of the modifications the state had requested, with a five-year extension of the “Arkansas Works” Medicaid demonstration waiver, which took effect in 2017 (more details below).

Under Arkansas Works, enrollees with income above the poverty level pay modest premiums for their coverage ($13/month in 2017, and 2% of household income starting in 2018; as noted above, premiums will no longer be charged after 2022), unemployed enrollees are referred to job training/referral, and enrollees can obtain coverage from their employers with supplemental funding from Medicaid.

But only about 20% of the 63,000 enrollees subject to premiums actually paid those premiums in 2017. (People who don’t pay the premiums are not disenrolled under the terms of Arkansas Works, and the state cannot send the overdue premiums to collections, place a lien on property, garnish wages, report the unpaid amounts to credit monitoring agencies, etc.). The state reported that of the people referred to job training, less than 5% followed through and obtained work referrals. And only one person ever used the Medicaid premium assistance program for employer-sponsored insurance.

Additional changes to Arkansas Medicaid expansion were approved by state lawmakers in May 2017, and Governor Hutchinson submitted an amendment to the state’s waiver in June 2017, which was under HHS review for several months. The proposed changes, detailed below, were mostly approved by the Trump administration, although the state’s proposal to cap Medicaid eligibility at the poverty level (instead of 138% of the poverty level) was rejected.

On March 1, 2017, amid concerns about the future of Medicaid expansion under the Trump administration, the Arkansas House of Representatives passed H.B.1465, which would have frozen Medicaid expansion enrollment as of July 1, 2017.

But a few weeks later, Republican leadership in the U.S. House of Representatives pulled the American Health Care Act without a vote, keeping the ACA intact for the time being (the bill later passed the House, but fell short in the Senate). The following week, the Arkansas Senate approved another year of funding for Medicaid expansion by passing S.B.196. The Arkansas House of Representatives passed it at the end of March, and Governor Asa Hutchinson signed it into law in early April.

Arkansas Works under the Trump administration: new rules approved by HHS

The Arkansas Works waiver allowed the state to continue to implement Medicaid expansion using private coverage, and to implement some modifications to the program. But some modifications — like a work requirement and an asset test — were not permitted by CMS under the Obama administration.

Governor Hutchinson had expressed his intent to continue to push for more modifications to Arkansas Works under the Trump administration. In March 2017, Hutchinson announced that he was directing the state Department of Human Services to draft a proposal to amend the Arkansas Works waiver. The changes he suggested included a work requirement, capping eligibility at the poverty level, instead of 138% of the poverty level, and allowing state control of eligibility determination, using a new computer system the state has put in place.

The Arkansas legislature passed S.B.3 and H.B.1003 in May 2017; Hutchinson signed them into law the next day. The bills called for Arkansas to seek a waiver from HHS allowing a work requirement for some Medicaid enrollees, and a Medicaid expansion eligibility cap of 100% of the poverty level. The legislation also called for the state to “study and analyze” small employer coverage in Arkansas, and determine ways to strengthen employer-sponsored insurance and help more businesses offer coverage to their workers.

The state’s waiver amendment proposal was submitted to HHS in June 2017, and although Hutchinson had initially hoped that the waiver would be approved in time for the changes to take effect in January 2018, a modified approval of the waiver proposal didn’t come until March 2018.

The waiver called for four basic changes to implement the reforms that Hutchinson had proposed:

- A work requirement (this was implemented in 2018, overturned by a judge in 2019, and approval was revoked by HHS in 2021)

- Capping eligibility at the poverty level, instead of 138% of the poverty level. For a single individual, the poverty level in 2018 was $12,140, while 138% of the poverty level was $16,753. This was the only aspect of the proposed amendments that the Trump administration did not approve.

- Elimination of the Arkansas Works employer-sponsored insurance premium assistance program (this was put in place by the initial Arkansas Works waiver, but it was only ever used by one enrollee).

- Eliminating retroactive eligibility, unconditionally. Federal Medicaid rules allow new enrollees to be covered for medical expenses that were incurred up to 90 days before they enrolled, and Arkansas wanted to mostly eliminate that provision. CMS had already approved the elimination of retroactive eligibility in Arkansas (with coverage simply back-dated to the first of the month during which the person applies, rather than 90 days before the application date), but with conditions attached, requiring the state to come into compliance with eligibility determination requirements. The state’s amendment to the Arkansas Works waiver asked CMS to remove those conditions and simply let the state eliminate retroactive eligibility for Medicaid without making any other changes to protect consumers’ access to coverage.

On March 5, 2018, the Trump administration approved most of the state’s proposed changes, although they did not approve the reduced cap on Medicaid eligibility.

- The community engagement requirement was approved, and was phased in starting in June 2018. (As noted above, a federal judge halted the program in March 2019, and the Biden administration withdrew the waiver approval in 2021.) Medicaid enrollees who weren’t exempt from the requirement would have had to complete at least 80 hours per month of work, volunteering, community service, education, or job training, and report this information to the state each month. People who failed to report their community engagement for three months were disenrolled from Medicaid for the rest of the calendar year (ie, for up to nine months, which would have been a significant lock-out window).

- The Arkansas Works employer-sponsored insurance premium assistance program was eliminated under the terms of the waiver, but as noted above, it was essentially unused, so this was not a significant change.

- Retroactive eligibility for Medicaid coverage is set at 30 days in Arkansas. So a person who enrolls in Medicaid can have coverage backdated to 30 days before the application date, but no earlier than that. Federally, there’s a 90-day retroactive eligibility period, but CMS noted that the Arkansas waiver would allow them to test “whether eliminating 2 of the 3 months of retroactive coverage will encourage beneficiaries to obtain and maintain health coverage, even when they are healthy.”

- Notably, the waiver did not require Arkansas to give hospitals an opportunity to use presumptive Medicaid eligibility. In public comments on the earlier Arkansas Works waiver, consumer advocates had expressed grave concerns about the state’s efforts to eliminate retroactive eligibility, particularly given that Arkansas does not have a presumptive eligibility program in place. Commenters noted that the elimination of retroactive eligibility would simply result in cost-shifting from the Medicaid program to low-income residents and their health care providers, and would do nothing to improve the population’s overall health.

The waiver approval noted that Arkansas Works’ voluntary work referral program had not been effective as far as CMS and the state were concerned, with only a tiny fraction (4.7%) of beneficiaries referred to the program actually following through and accessing the work referral services (23% of those individuals subsequently obtained a job). The state was hoping that an actual work requirement—as opposed to a voluntary work referral program—would be more effective.

There was little doubt that it would have been effective in reducing the overall cost of the Medicaid program, as it was clear that fewer people would have coverage once the work requirement was implemented (indeed, 18,000 people lost coverage in the second half of 2018). But there was little evidence that it would actually result in a healthier population, which was one of the stated goals of the program. And in hindsight, the program was also woefully ineffective at actually getting people to newly-report community engagement.

Capping eligibility at the poverty level instead of 138% of the poverty level would have made 60,000 Arkansas Works enrollees ineligible for coverage. They would have been switched instead to regular premium subsidies (and cost-sharing subsidies if they picked Silver plans) for plans purchased in the exchange. However, their premiums and out-of-pocket medical costs, even after subsidies, would have been substantially more than they are with Medicaid, making coverage and health care unaffordable for some of them.

(There would have been cost-savings for the state, however, as Medicaid expansion is partially funded by the state, with a 90/10 federal/state split, whereas premium subsidies and cost-sharing reductions in the marketplace are funded entirely by the federal government.)

Similar program, new name

After 2016, Medicaid expansion in Arkansas was called “Arkansas Works” instead of the Private Option. But it was widely noted that the fundamental mechanics of the new program were very similar to the Arkansas Health Care Independence Program, which was the name of the Arkansas waiver program from 2014 through 2016. And that’s still the case with the Arkansas Health and Opportunities for Me (ARHOME) waiver that the state began using as of 2022. Arkansas still uses Medicaid funds to purchase private coverage for eligible enrollees in the exchange, which was the basic premise of the Private Option in the first place.

But lawmakers who were opposed to the Private Option were able to “end” it and replace it with “Arkansas Works” in 2017 — in many cases, fulfilling campaign promises but without the ramifications that would have ensued if the state had kicked 300,000+ people off their health insurance (that’s what would happen if they were to truly end Medicaid expansion).

Arkansas Works

Lawmakers considered an extension of Medicaid expansion during a special legislative session in April 2016, prior to the regularly-scheduled session. Arkansas Works was approved, but the funding details still had to be sorted out at that point.

In April 2016, the Arkansas Senate narrowly rejected SB121, the legislation that would continue funding for Arkansas Medicaid, including Arkansas Works. The bill was then sent back to committee, where it was amended to add a sunset provision for Arkansas Works, ending the program on December 31, 2016. This was a circuitous route to ultimately extending Medicaid expansion, as it essentially required Democratic lawmakers to vote to end Medicaid expansion – and opponents of Medicaid expansion get to also say that they voted to end Medicaid expansion – although they were relying on the Governor’s line-item veto power to preserve Medicaid expansion.

That version was approved by the Senate on April 20, in a 27 – 2 vote. It needed 27 votes to pass. The previous version of the bill — without the sunset amendment — had garnered 25 votes, falling short by only two votes.

SB121 quickly passed in the House as well, and was sent to Hutchinson for his signature, with lawmakers counting on Hutchinson’s promised line-item veto of anything that would end Arkansas Works. Hutchinson did employ the line-item veto to prevent Medicaid expansion from ending, and SB121 became law (Act 3) in May 2016.

The only remaining hurdle at that point was obtaining approval from CMS to implement the changes called for in Arkansas Works. In December 2016, CMS granted a five-year approval for Arkansas Works, and the state’s Medicaid expansion program continued — with some modifications — in 2017 (as noted above, Arkansas is seeking CMS approval to implement new modifications to Arkansas Works in 2018).

The notable modifications under Arkansas Works were:

- Premiums for people with income above the poverty level. Premiums could not exceed 2% of income, and enrollees were not dropped from the plan if they didn’t pay the premiums (the premium was $13/month in 2017, but grew to 2% of income in 2018 and beyond; as noted above, there are no longer premiums under ARHOME as of 2023).

- Job training referrals for unemployed enrollees (this transitioned to a work requirement under the Trump administration, although that was halted by a federal judge as of 2019 and rescinded by the Biden administration in 2021).

- Some Medicaid-eligible residents who have the option for coverage through an employer use the employer coverage, with Medicaid funds used to ensure that the costs for the enrollee are no more than they would have been under Medicaid. Hutchinson noted that this was the one area that CMS modified the provisions in the state’s waiver proposal, limiting the premium assistance program for employer-sponsored insurance to employers that are newly offering coverage. Under the Trump administration, Hutchinson was initially pushing to allow this for any employer-sponsored plan for enrollees who earn between 75% and 100% of the poverty level, but the final waiver amendment called for eliminating the employer-sponsored insurance premium assistance program altogether, since it had remained essentially unused.

- People would be covered by Medicaid once they enroll, with no 90-day retroactive coverage (CMS made this conditional in the original Arkansas Works waiver, but the state later received approval to eliminate the retroactive coverage provision unconditionally).

CMS put a cap on the total per-person amount that they would pay for the Private Option/Arkansas Works, in order to ensure that the privatized version of Medicaid expansion wouldn’t cost the federal government more than an expansion of fee-for-service coverage. For 2017, the average per-enrollee cost approved by CMS increased to $570.50/month, which was a 9% increase over the per-enrollee cost in 2016. The higher costs are due to increasing prescription costs (a nationwide issue) and higher utilization of healthcare services among Arkansas Medicaid expansion enrollees.

Arkansas Medicaid history

Arkansas implemented Medicaid on Jan. 1, 1970. The program is administered by the Arkansas Division of Medical Services, which is part of the Arkansas Department of Human Services.

As with nearly all other states, Arkansas provides Medicaid services to some beneficiaries through managed care arrangements. According to KFF, about half of Arkansas Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in Medicaid managed care or primary care case management programs as of 2021. These arrangements are a strategy to help states improve the quality of care provided and control costs.

With Arkansas’ decision to expand Medicaid, 55% of the state’s 510,000 uninsured residents (as of 2014) were eligible for Medicaid according to KFF.

Footnotes

- “October 2023 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights”, Medicaid.gov, Accessed February 2024 ⤶

- Total Monthly Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment and Pre-ACA Enrollment, KFF.org, Accessed February 2024 ⤶ ⤶

- Unwinding data for April, May, June, July, August, and September. Arkansas Department of Human Services. Accessed December 2023. ⤶ ⤶

- ”Arkansas dental insurance guide 2023” healthinsurance.org, Accessed September 2023 ⤶

- “Medicare Monthly Enrollment” CMS.gov, April 2023 ⤶

- “Availability of short-term health insurance in Arkansas” healthinsurance.org, Sept. 7, 2023 ⤶

- Arkansas Department Of Human Services Completes Six-Month Medicaid Unwinding. Arkansas Department of Human Services. October 2023. ⤶

- Arkansas Health and Opportunity for Me (ARHOME). Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed January 2024. ⤶

- Request to Amend the ARHOME Section 1115 Demonstration Project Project No. 11-W-00365/4. State of Arkansas, Department of Human Services. June 2023. ⤶