Medicaid eligibility and enrollment in Kansas

New Medicaid expansion bills include a work requirement in an effort to win over GOP lawmakers

Who is eligible for Medicaid in Kansas?

Kansas Medicaid, which is called KanCare, is available to individuals who meet the following income limits (plus an extra 5% in most cases, as an income disregard):

- Children up to age 1 are covered with family income up to 166% of the federal poverty level (FPL)

- Children ages 1 to 5 are covered with family income up to 149% of FPL

- Children ages 6 to 18 are covered with family income up to 133% of FPL

- Pregnant women with family income up to 166% of FPL (coverage for the mother continues for 12 months after the baby is born)

- Parents with dependent children are eligible with household income up to 33% of FPL

- Children with family income too high to qualify for Medicaid but not more than 227% of FPL are eligible for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

- Individuals who are elderly or disabled may also qualify for Kansas Medicaid; Learn more here about how Kansas Medicaid helps low-income residents who are also enrolled in Medicare

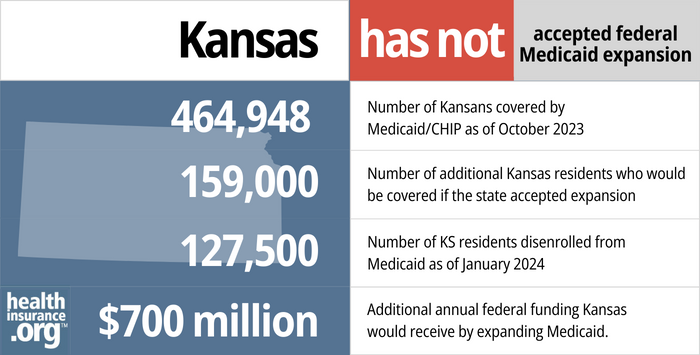

Kansas has not implemented Medicaid expansion for adults with income up to 138% of the federal poverty level. As a result, childless, non-disabled, non-elderly adults are not eligible for coverage regardless of how low their income is, and parents with dependent children can only qualify if they live in extreme poverty.

Legislation to expand Medicaid in Kansas has been considered several times in recent years. New Medicaid expansion legislation was introduced in the Kansas Senate (S.B.355) and House (H.B.2556) in January 2024.1 Medicaid expansion legislation has been unsuccessful in previous years (although some bills have come close, as explained below), but the 2024 bills include work requirements, offered as a compromise solution by Governor Laura Kelly.2

for 2026 coverage

0.0%

of Federal Poverty Level

Apply for Medicaid in Kansas

Children and families can apply online. Anyone needing assistance with the application process can call 1-888-369-4777 for help.

Eligibility: Children up to age 1 with family income up to 166% of FPL. Children ages 1-5 with family income up to 149% of FPL. Children ages 6-18 with family income up to 133% of FPL; children with family income up to 242% of FPL are eligible for CHIP.

Has Kansas expanded Medicaid?

Kansas is one of only ten states where the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid still has not been implemented as of 2024. As a result, the state has an estimated 44,000 low-income residents who are stuck in the “coverage gap,” meaning that they earn too little to qualify for subsidized private health coverage, but are also ineligible for Medicaid because the state has refused to accept federal funding to expand Medicaid.

Legislative attempts to expand Medicaid have repeatedly failed in Kansas. The most recent Medicaid expansion legislation bills (S.B.355 and H.B.2556) were introduced in the Kansas Senate and House in January 2024, but their future is uncertain.1

The 2024 bills include work requirements, in a compromise solution offered by Governor Laura Kelly.2 They do differ from previous work requirement bills that many states have considered, in that they call for proof of employment to enroll in Medicaid (unless exempt), but not a specific number of hours that the person must work. Proof of employment can include a W-2, 1099, pay stub, etc. (one of the exemptions is proof of volunteering at least 20 hours per week).

Legislation to expand Medicaid passed in 2017, but then-Gov. Sam Brownback vetoed it. Medicaid expansion legislation passed again in the Kansas House in 2019, but died in the Senate. In 2020, Medicaid expansion legislation was announced as a bipartisan compromise by Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly and Republican Senate Majority Leader Jim Denning, but ultimately failed to pass.

The legislation that was introduced in the Kansas House in 2022 did not advance out of committee. And neither did the bills that were introduced in 2023 (H.B.2415 and S.B.225).

Although Kansas has not implemented the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, the state did implement the American Rescue Plan provision that allows states to extend postpartum Medicaid coverage to 12 months (postpartum Medicaid coverage previously ended 60 days after the baby was born). In Kansas, the postpartum Medicaid coverage extension took effect in April 2022.

Learn how states that expanded Medicaid might reduce spending on Medicaid.

- 464,948 – Number of Kansans covered by Medicaid/CHIP as of October 20233

- 159,000 – Number of additional Kansas residents who would be covered if the state accepted expansion4

- 127,500 – Number of KS residents disenrolled from Medicaid as of January 20245

- $700 million – Additional annual federal funding Kansas would receive if the state expanded Medicaid6

Explore our other comprehensive guides to coverage in Kansas

Use this guide to help you find the right health plan in Kansas. Many people find an ACA Marketplace plan, also known as Obamacare or exchange, to be a cost-effective choice.

Looking for a brighter smile? Learn about dental coverage options in Kansas.

As of early 2023, there were 571,968 Medicare beneficiaries in Kansas.7 Use our guide to learn about Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and Medigap offerings in Kansas.

You can buy short-term health insurance in Kansas for up to a year, and it can be renewed once. So the longest you can have short-term health coverage in Kansas is two years.8

Frequently asked questions about Kansas Medicaid eligibility and enrollment

How do I enroll in Medicaid in Kansas?

For children and families:

- Apply on the KanCare Medical Self-Service portal (you will need to login or create an account) or on the Healthcare.gov website (if you are under 65 years old).

- Complete an application. Call 1-800-792-4884 for help determining which application to use or to have an application mailed to you. The form describes options for returning the form.

- If you need help with the application process, contact DCF toll free at 1-888-369-4777.

For elderly or disabled individuals:

- Apply on the KanCare Medical Self-Service portal (you will need to login or create an account).

- Complete an application. Call 1-800-792-4884 for help determining which application to use or to have an application mailed to you. The form describes options for returning the form.

How is Kansas handling Medicaid renewals after the pandemic?

Under federal rules, states were not allowed to disenroll anyone from Medicaid between March 2020 and March 2023. But that rule ended March 31, 2023, allowing disenrollments to resume. Eligibility for all Medicaid enrollees must be checked during a year-long “unwinding” period that began in the spring of 2023.

By January 2024, KFF reported that about 127,500 people had been disenrolled from KanCare, while coverage had been renewed for about 191,300 enrollees.5

Many states have continued to send out renewal forms during the pandemic (without disenrolling anyone), but Kansas has not. The state began to mail renewal packets in mid-March 2023. KanCare renewals were scheduled to be somewhat frontloaded during the unwinding period, with 11% or 12% of enrollees’ eligibility redetermined in each of the first several months, tapering off to only about 4% of enrollees’ eligibility being redetermined in the final months.

An enrollee’s KanCare coverage will remain in force until their renewal date, but could end at that point if they’re no longer eligible or if they fail to complete their renewal forms. So it’s essential to make sure that your address on file with KanCare is up-to-date, and to promptly respond to any information requests you receive from them.

If you’re no longer eligible for KanCare, you can transition to an employer’s plan (if available) or to a plan offered via the Kansas Marketplace/exchange (HealthCare.gov). In both cases, your loss of Medicaid will trigger a special enrollment period that will allow you to sign up for new coverage. To avoid a gap in coverage, it’s important to submit your enrollment before the date your KanCare coverage ends, since your new plan (from an employer or the marketplace) won’t have retroactive coverage.

How many people are enrolled in Medicaid in Kansas?

As of July 2013, enrollment in Kansas Medicaid/CHIP was 378,160. By September 2023, it stood at 493,565.9 Virtually all of that increase has come since the COVID pandemic began in 2020, but enrollment is decreasing again during the “unwinding” of the continuous coverage rule that prevented disenrollments for three years during the pandemic.

Legislation impacting Kansas Medicaid

Bipartisan Medicaid expansion legislation was considered in 2020 but did not pass

Although Kansas was considered a state to watch for Medicaid expansion legislation in 2020, the bill was ultimately unsuccessful.

Two bills were pre-filed for consideration during the 2020 session. S.B.246 was pre-filed in early December 2019. It included monthly fees that could be as high as $25 per enrollee, and would refer unemployed Medicaid expansion recipients to a job training program. And S.B.252, which was pre-filed in January, just before the start of the legislative session, was announced as a bipartisan compromise by Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly and Republican Senate Majority Leader Jim Denning, arousing hopes that Kansas will be the next state to expand Medicaid.

But then-Senate President, Susan Wagle (R, Wichita) was opposed to Medicaid expansion, and refused to allow it to come up for a vote in the Senate unless both chambers of the legislature passed a constitutional amendment that would have overturned the Kansas Supreme Court ruling that protects a woman’s access to abortion in Kansas.

At that point, abortion access was still legally protected nationwide under Row v. Wade, but abortion opponents were hoping that could be overturned at the federal level by the Supreme Court (which did happen in 2022). The Kansas court ruling upholds a woman’s right to choose in Kansas, regardless of federal rules. But Wagle and other anti-choice Republicans in Kansas would like to see that changed, and blocked the 2020 Medicaid expansion legislation in an effort to try to pass the abortion amendment.

Senate Democrats made a last-ditch attempt to bring the Medicaid expansion measure up for a vote in May, but were unsuccessful as a result of procedural rules. Denning expressed that he was “profoundly disappointed” that the bill never received a floor debate during the 2020 session.

Senator Barbara Bollier, M.D. who was among the sponsors for both Medicaid expansion bills, wrote an article on our site in 2017 about the importance of Medicaid expansion and her tireless efforts to convince other Kansas lawmakers to expand coverage. Bollier was a Republican at that point, but became a Democrat in 2018 and unsuccessfully ran for election to the US Senate in the 2020 election. Wagle was vying for the Republican nomination to run against Bollier, but dropped out in May 2020.

Details of the bipartisan Medicaid expansion proposal that was introduced in 2020

A summary of the bipartisan Medicaid expansion legislation (S.B.252) is available here. In a nutshell, here is what was being proposed, although the legislation was ultimately unsuccessful:

- Full Medicaid expansion, as outlined in the ACA, would have taken effect as of January 2021.

- Kansas would have conducted an actuarial study related to reinsurance and the possibility of switching people with income between 100 and 138% of the poverty level back to the exchange (this group is already eligible for coverage in the exchange — it’s only people under the poverty level who are in the Medicaid coverage gap — but they would have transitioned to Medicaid as of 2021 under the terms of S.B.252).

- By 2021, Kansas would have submitted a 1332 waiver to CMS, seeking to implement a reinsurance program. Reinsurance programs lower premiums across the board in the individual market, although the lower premiums are really only felt by people who pay full price for their coverage. For those who get subsidies (which includes the large majority of enrollees), the subsidy amounts decline along with premiums — in some cases, people who get subsidies end up paying more with a reinsurance program in place.

- At the same time, Kansas would submit an 1115 waiver to CMS, seeking approval to switch people earning 100-138% of the poverty level back to the exchange. If approved, this waiver would essentially mean that this population would have gone from private, subsidized plans in the exchange in 2020, to Medicaid in 2021, and back to private subsidized plans in the exchange in 2022.

- The plan to seek approval to transition people above the poverty level back to private insurance was a nod to conservative Medicaid expansion proposals, and was part of the bipartisan appeal of S.B.252. But this proposal was much less likely to be approved, as CMS has not yet approved it anywhere, despite some states efforts. (Most recently, Utah tried to receive Medicaid expansion funding while only expanding coverage to 100% of the poverty level, and CMS said no. Utah ultimately agreed to fully expand coverage, to 138% of the poverty level, in order to get full Medicaid expansion funding from the federal government.)

- And the legislation clarified that if CMS doesn’t approve the 1115 waiver (or the 1332 waiver, although that’s much less likely to be an issue), full Medicaid expansion would continue in Kansas.

- Unemployed Medicaid expansion enrollees would be referred to the Kansas Works Program (this is a work referral program, as opposed to a work requirement; people would receive assistance with job training and securing work, but would not lose their health insurance as a result of not having a job).

- Premiums of up to $25/month could be charged for people with income above the poverty level. But people would not have beenlocked out of Medicaid expansion for failure to pay the premiums (instead, they’d have been subject to collection under the rules for debts owed to the state of Kansas). The $25/person fee would be allowed to amount to as much as $100 per month per family, but children under the age of 19 are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP in Kansas with family incomes as high as 230% of the poverty level, so they would not be subject to the fee, as they would not be newly-eligible for Medicaid under the expansion rules.

- As explained here by Charles Gaba and Dave Anderson (when Kansas considered similar legislation in 2019), a fee of $25/month would put some low-income Kansans in a worse financial spot than they currently have with subsidized coverage in the exchange. But non-disabled, non-pregnant adults without minor children are not currently eligible for Medicaid at all in Kansas if their income is below the poverty level. So even with a fee, Medicaid expansion would be better for them than the status quo. It’s also worth noting that the legislation includes a stipulation that monthly premiums for Medicaid expansion enrollees could not exceed 2% of income (it’s not clear, however, if the $25/month “fee” would is considered a premium). For a single person, that would amount to a premium cap of less than $25/month as long as their income didn’t exceed $15,000/year.

Medicaid expansion passed the House in 2019 but died in the Senate

H.B.2066, which called for Medicaid expansion, passed in the Kansas House in March 2019 by a vote of 69-54 (note that the bill was revised; it initially dealt with nursing regulations, but that text was replaced with the Medicaid expansion text in the final version). But it never reached a floor vote in the Senate, as explained here by Kansas Representative Brett Parker. H.B.2066 included a job training referral program and a monthly fee of up to $25 for Medicaid expansion enrollees.

2017: House and Senate passed expansion but Governor Brownback vetoed it

In September 2016, Sandy Praeger, a Republican and former Kansas Insurance Commissioner, called on Governor Brownback and Kansas lawmakers to expand Medicaid, saying that there was “no logical explanation” for the state’s continued rejection of federal funding for Medicaid expansion, and noting that the decision has been based on politics rather than cost analysis.

And the state’s primary election in August 2016 resulted in several moderate Republicans getting onto the ballot for November, energizing Medicaid expansion advocates. Supporters became more confident than ever that they could get a bill passed in 2017 to expand coverage, particularly given that several of the primary winners had been outspoken about their support for Medicaid expansion.

On February 23, 2017, H.B.2044 passed the Kansas House of Representatives, 81-44. A month later, the bill passed the Senate, 25-14. But then-Governor Sam Brownback remained steadfast in his opposition to Medicaid expansion, and vetoed the bill. Although the Medicaid expansion legislation passed by a wide margin in both chambers, it was a few votes shy of a veto-proof majority.

On April 3, the House voted to uphold Brownback’s veto. The final margin was 81-44, three votes shy of the 84 votes that would have been necessary to override the Governor’s veto. Two representatives who had voted for expansion ended up voting to uphold the veto, while two others who had opposed the expansion vote shifted sides and voted to override the veto. In the end, the numbers ended up the same as they had been the prior week, and the governor’s veto remained in effect.

Brownback listed several reasons for vetoing H.B.2044:

- He wanted Medicaid reform to eliminate the existing waiting lists for disabled Kansans (a population that was already eligible for Medicaid pre-ACA)

- He wanted Medicaid reform to be budget neutral for the state (expanded Medicaid is funded almost entirely by the federal government, but states began paying 5% of the cost in 2017, and that has grown to 10% in 2020 and future years).

- He wanted a work requirement for able-bodied adults (as opposed to the work referral program in H.B.2044)

- He wanted Medicaid reform to cut funding for Planned Parenthood, and H.B.2044 did not do that.

- He believed it would be “unwise” to expand Medicaid given the uncertainty of the ACA on the federal level (ultimately, the ACA has remained in place; efforts to repeal it legislatively have failed, and the Supreme Court has upheld the law three times)

In 2014, Brownback signed legislation (H.B.2552) that required legislative approval to expand Medicaid (as opposed to allowing it via executive action, which is the path that governors in some states have used to expand Medicaid without having to obtain approval from lawmakers). H.B.2552 was popular with Brownback and 2014’s more-conservative legislature, particularly given the strong-than-anticipated gubernatorial campaign of then-House Minority Leader, Paul Davis — a Democrat who supported Medicaid expansion.

The American Cancer Society, which supports Medicaid expansion, reported that 82% of Kansas survey respondents wanted the state to accept federal funding to expand Medicaid. Hospital leaders in Kansas also pushed hard for Medicaid expansion, noting that without expansion, some rural hospitals would be forced to close. Although the measure passed by a wide margin in both chambers, it simply wasn’t enough to overcome the governor’s veto.

Lawmakers again considered Medicaid expansion during the 2018 legislative session, although the bill did not pass. Jeff Colyer, who assumed the Governor’s office in January 2018 when Brownback left the join the Trump Administration, was also opposed to Medicaid expansion in the state, and would have been likely to veto an expansion bill, just as Brownback did.

The Senate Public Health and Welfare Committee passed the 2018 Medicaid expansion bill (S.B.38) in February, but it did not advance after that. House Democrats also tried amending other 2018 bills, including a budget bill, to include Medicaid expansion, but were unsuccessful.

KanCare 2.0 waiver proposal initially called for a work requirement and 36-month cap on Medicaid benefits. CMS rejected the 36-month cap and Kansas withdrew the work requirement

The KanCare Medicaid program operates with a waiver from CMS that must be periodically extended. The state was given a temporary extension, through the end of 2018, but was in need of a longer-term renewal by the end of 2018. The state’s initially proposed KanCare renewal, dubbed KanCare 2.0, called for a work requirement for able-bodied, non-exempt adults, and would also have imposed a 36-month limit on Medicaid eligibility for adults who were subject to, and in compliance with, the work requirement (those who do not comply with the work requirement would lose access to Kansas Medicaid after just three months).

In May 2018, CMS notified Kansas that the 36-month cap on Medicaid eligibility would not be allowed. The federal government was still considering the rest of the state’s proposal at that point, but the letter indicated that CMS was likely to approve the state’s proposed work requirements, and reiterated the fact that CMS has been willing to approve lock-out periods for people who don’t comply with work requirements, which was part of Kansas’ proposal.

But the KanCare extension approval, granted in late 2018 by CMS, noted that the state had asked CMS to defer consideration of the work requirement. The Colyer administration clarified that the state legislature had determined that a work requirement would need to go through the budget process, and would thus not be implemented as part of the KanCare extension that took effect in 2019.

Hospital closure puts a spotlight on Medicaid expansion

In October 2015, Mercy Hospital in Independence, Kansas announced that it would close, becoming the first Kansas hospital to shut down in nine years. The hospital’s closure was linked to the state’s rejection of Medicaid expansion. In states that don’t expand Medicaid, the uninsured rate remains higher and hospitals continue to struggle with higher levels of uncompensated (charity) care – particularly since federal funds to offset uncompensated care costs are being phased out now that states have the option to expand Medicaid.

Mercy Hospital’s announcement triggered renewed calls for Medicaid expansion in Kansas, but the Brownback Administration and the Colyer Administration remained steadfast in their refusal to expand Medicaid to all adults with household income up to 138% of the poverty level. In response to editorials calling for Medicaid expansion in the state, an email from Brownback’s deputy communications director Melika Willoughby described Medicaid expansion as “morally reprehensible” and an “Obamacare ruse [that] funnels money to big city hospitals.” The email also said that Medicaid expansion would create a new entitlement “for able-bodied adults without dependents, prioritizing those who choose not to work before intellectually, developmentally, and physically disabled, the frail and elderly, and those struggling with mental health issues.” (This is disingenuous, as 60% of adults in the coverage gap are in an employed household; the problem is that their jobs are low-paying and don’t provide health insurance.)

But then-State Senator Jeff King, a Republican, who was vice president of the Kansas Senate until 2017 (King did not seek re-election in 2016), represented the district where Mercy Hospital is located, and was swift in his condemnation of Willoughby’s email. King supported Medicaid expansion, albeit with a waiver that would allow Kansas to use private health insurance to cover the newly-eligible population (this is an approach that Arkansas uses to implement Medicaid expansion; New Hampshire and Iowa also used it, but have since transitioned to regular Medicaid managed care. The Kansas Hospital Association also disagreed with Willoughby’s position, and has repeatedly called for Medicaid expansion in the state.

Footnotes

- Kansas Senate Bill 355 and House Bill 2556. BillTrack50. Introduced January 2024. ⤶ ⤶

- Kansas governor unveils revenue neutral Medicaid expansion plan with work requirement. Kansas Reflector. December 14, 2023. ⤶ ⤶

- ”October 2023 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights“, Medicaid.gov, Accessed February 2024 ⤶

- “3.7 Million People Would Gain Health Coverage in 2023 If the Remaining 12 States Were to Expand Medicaid Eligibility” , urban.org, Accessed July 2022 ⤶

- Medicaid Enrollment and Unwinding Tracker. KFF. Accessed January 2024. ⤶ ⤶

- Kansas governor unveils revenue-neutral Medicaid expansion plan with work requirement. Kansas Reflector. December 2023. ⤶

- “Medicare Monthly Enrollment” CMS.gov, April 2023 ⤶

- “Kansas Statutes Chapter 40. Insurance § 40-2,193. Specially designed policies; short-term policies” Findlaw.com, Jan. 1, 2020 ⤶

- September 2023 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights. Medicaid.gov, Accessed January 2024. ⤶