Medicaid eligibility and enrollment in Maine

Medicaid (MaineCare) expansion took effect in early 2019; More than 109,000 people were enrolled in expanded Medicaid by 2023

Who is eligible for Medicaid in Maine?

Medicaid in Maine is called MaineCare. Coverage is available to various low-income populations, and also to elderly or disabled residents who meet both income and asset limits. Maine residents who meet the following income limits qualify for Medicaid in Maine (all of these limits include the built-in five percent income disregard that used for income-based Medicaid eligibility):

- Children up to 1-year-old: 196% of the federal poverty level (FPL)

- Children age 1 to 18: 162% of FPL; children with family income up to 213% of FPL qualify for the Children’s Health Insurance Program

- 19 and 20-year-olds: 161% of FPL

- Pregnant women: 214% of FPL

- Adults under age 65: 138% of FPL

- For adults over age 65 and people who qualify based on a disability or blindness, there are both income and asset limits.

for 2026 coverage

0.0%

of Federal Poverty Level

Apply for Medicaid in Maine

Go to MyMaineConnection to apply online. Print an application and mail it 114 Corn Shop Lane, Farmington, ME 04938. Call 1-855-797-4357 to enroll by phone. Visit your local Maine DHHS Office for in-person assistance.

Eligibility: Low-income aged, blind, and disabled residents. Children up to 1 year old with household income up to 191% of FPL. Children ages 1-18 with household income up to 157% of FPL; children with family income up to 208% of FPL qualify for the Children’s Health Insurance Program. 19 and 20-year-olds with household income up to 156% of FPL; pregnant women with household income up to 209% of FPL; adults under age 65 with household incomes up to 138% of FPL.

When did Maine expand Medicaid eligibility?

Medicaid expansion took effect in early 2019, with coverage retroactive as far back as July 2018 for people who had already applied for coverage. As detailed below, voters passed a Maine Medicaid expansion ballot initiative in November 2017, and coverage was to be effective by July 2018. But former Governor Paul LePage was adamantly opposed to Medicaid expansion, and he spent all of 2018 refusing to adhere to the will of the voters on this issue.

Governor Janet Mills, a Democrat, took office on January 2, 2019. Her first executive order, signed on January 3, instructed the Maine Department of Health and Human Services to work with the federal government to implement Medicaid expansion no later than February 1, 2019. Maine became the 33rd state to expand Medicaid.

The order also noted that the state would “work expeditiously towards resolving issues affecting those who applied for coverage between July 2, 2018 and January 2, 2019.” That was a nod to the Mills administration’s plan to provide retroactive coverage to people who would have been covered starting as early as July 2, 2018, if not for the LePage administration’s obstruction of Medicaid expansion.

CMS officially approved Maine’s Medicaid expansion plan in April 2019. The approved expansion effective date was retroactive to July 2, 2018, so people who had applied for coverage prior to 2019 were granted retroactive effective dates based on when they had applied. More than 6,000 people had applied for coverage in the second half of 2018 (consumer advocacy groups had been encouraging eligible residents to enroll, as they knew there was a possibility of retroactive coverage eventually being granted).

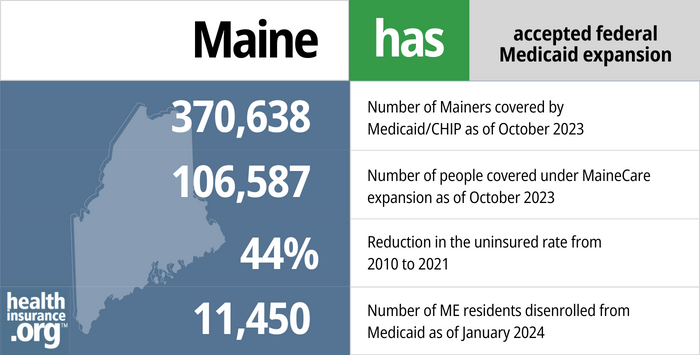

- 370,638 – Number of Mainers covered by Medicaid/CHIP as of October 20231

- 106,587 – Number of people covered under MaineCare expansion as of October 20232

- 44% – Reduction in the uninsured rate from 2010 to 202134

- 11,450 – Number of ME residents disenrolled from Medicaid as of January 20245

Explore our other comprehensive guides to coverage in Maine

This guide is designed to help you understand your health insurance options in Maine, and we’ve included answers to numerous frequently asked questions.

Looking to improve your smile? Dental insurance may be a smart addition to your health coverage. Our guide explores dental coverage options in Maine.

In Maine, 367,991 residents were enrolled in Medicare in early 2023.6 Our Maine Medicare guide explains what you need to know about Medicare coverage options and Medicare regulations in the state.

Although Maine technically allows the sale of short-term health plans, there are currently no insurers offering these plans in Maine.7

Frequently asked questions about Maine Medicaid eligibility and enrollment

How do I enroll in Medicaid in Maine?

Maine’s Medicaid program is called MaineCare. If you think you may qualify, here is how you can submit an application.

- Go to HealthCare.gov or MyMaineConnection to apply online (if you are 65 or older or have Medicare, use the MyMaineConnection site to apply)

- Print an application and mail it 114 Corn Shop Lane, Farmington, ME 04938.

- Call 1-855-797-4357 to enroll by phone.

- Visit your local Office of Maine’s Department of Health and Human Services (OFI) for in-person assistance.

How does Medicaid provide assistance to Medicare beneficiaries in Maine?

Many people with Medicare receive help through Medicaid with the cost of Medicare premiums, prescription drug expenses, and costs that Medicare doesn’t cover — such as long-term care.

Our guide to financial resources for Medicare enrollees in Maine provides an overview of those programs, including Medicare Savings Programs, long-term care benefits, and income guidelines for assistance.

How is Maine handling Medicaid renewals after the pandemic?

From March 2020 through March 2023, states were prohibited from disenrolling anyone from Medicaid, with very limited exceptions. Due in large part to this COVID-related continuous coverage rule, MaineCare enrollment grew by 40% since early 2020. Federal rules ended the ban on disenrollments as of March 31, 2023, and required states to begin a year-long “unwinding” process during which every Medicaid enrollees’ eligibility is rechecked. States could begin that process in February, March, or April 2023, and Maine opted for April.

The state’s first round of renewal notices, for people with a May renewal date, were mailed out in late April and were due back by the end of May. The first round of disenrollments will come at the end of June, for people who are no longer eligible and people who failed to respond to their renewal notice. This process will then be repeated throughout the coming year, with eligibility being redetermined for approximately 31,000 members per month.

This page has answers to FAQs about Maine’s process of returning to normal eligibility redeterminations and disenrollments. It’s essential for MaineCare enrollees to make sure that their correct contact information is on file with the state Medicaid office, as coverage will terminate if the state is ultimately unable to get in touch with an enrollee in order to renew their coverage.

People who lose MaineCare coverage during the “unwinding” period will be able to transition to an employer’s plan or Medicare, if eligible. The enrollment opportunity for an employer’s plan generally only continues for 60 days after the loss of Medicaid. But there’s a six-month window to transition to Medicare.

People who aren’t eligible for either of those options will be able to transition to a private plan through CoverME, the state’s health insurance exchange/marketplace. And CoverME has announced a special enrollment period, through July 31, 2024, for people who lose Medicaid at any time during the “unwinding” of the COVID-era continuous coverage rules. A similar special enrollment period is available in states that use HealthCare.gov, but it’s optional for states that run their own exchange, like Maine, to offer this sort of extended special enrollment opportunity.

How many people are enrolled in Medicaid in Maine?

Maine Medicaid (MaineCare) enrollment stood at more than 410,000 people as of early 2023. More than a quarter of those enrollees — 106,509 people — were enrolled under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion guidelines that took effect in 2019 in Maine.

Legislation impacting Maine Medicaid

Voters approved Medicaid expansion in 2017, but Governor LePage blocked implementation throughout 2018

Lawmakers in Maine had been trying for years to accept federal funding to expand Medicaid and provide coverage for the state’s lowest-income residents (some of these people were eligible for premium subsidies in the exchange pre-expansion, but people with income under the poverty level were in the coverage gap created by the Governor’s refusal to expand Medicaid). Over the years, lawmakers passed five bills that called for expanding Medicaid, but Gov. LePage’s ongoing opposition on the issue was an insurmountable stumbling block. LePage vetoed all five Medicaid expansion bills, and lawmakers did not have the votes to override his vetoes.

After years of battling with the governor, advocates for Medicaid expansion in Maine took the issue to the voters in the 2017 election. The Maine secretary of state announced in February 2017 that the initiative to expand Medicaid had garnered enough signatures to appear on the November 2017 ballot. But the wording of the ballot initiative became a point of contention, with proponents of Medicaid expansion calling it “insurance” and opponents — including LePage — insisting that it be called “welfare” or something similar.

Ultimately, the wording of the ballot initiative was changed to “coverage” and the official language of Maine Question 2 was as follows:

“Do you want Maine to expand Medicaid to provide healthcare coverage for qualified adults under age 65 with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level, which in 2017 means $16,643 for a single person and $22,412 for a family of two?”

Question 2, the Medicaid Expansion Initiative, was approved, with 59% of voters supporting Medicaid expansion.

Unlike some other states that have used 1115 waivers to expand Medicaid with state-specific guidelines, Question 2 initiated a straightforward expansion as called for under the ACA, so Maine’s Department of Health and Human Services essentially just had to inform HHS, with a state plan amendment, that their Medicaid program would expand as called for in the ACA, rather than requesting HHS approval to create a unique approach to expansion.

Under the terms of the ballot initiative, Maine had until April 3, 2018 to submit a state plan amendment to the federal government, outlining their plan to expand Medicaid. And they had until July 2 to start enrolling eligible Maine residents in expanded Medicaid. This was required under state law with the passage of the ballot initiative, and no legislation was necessary in order to move forward with expansion.

But April 3 came and went, and Gov. LePage’s administration did not submit a Medicaid expansion proposal to CMS. LePage steadfastly refused to expand Medicaid — even after the ballot initiative passed — until lawmakers come up with what he considered adequate funding (it’s noteworthy that LePage’s office cited a much higher state cost for Medicaid expansion than the projection from the Maine Office of Fiscal and Program Review), and LePage included several constraints in terms of what he’d allow as far as funding sources, saying that lawmakers couldn’t raise taxes or tap the state’s rainy day fund. Indeed, LePage even vetoed legislation in July 2018 that would have allocated funding for Medicaid expansion (in late December, a few days before leaving office, LePage called for taxing hospitals to pay for Medicaid expansion).

Maine received a one-time tobacco settlement of $35 million, which Mills suggested could be used to fund the state’s share of Medicaid expansion costs in the first year (at that point Mills was the Maine Attorney General; she has since become governor). The state also had $128 million in projected surplus revenue that could be used to fund expansion, but LePage pushed back against both suggestions. Medicaid expansion advocates were hoping for a legislative solution in April 2018, as opposed to a protracted legal battle, but they noted that if necessary, they would sue the LePage Administration in order to implement the legally binding ballot initiative.

The 2018 legislative session ended without an agreement on Medicaid expansion funding, and on April 30, a lawsuit was filed against the Maine Department of Health and Human Services. The plaintiffs in the case included two consumer advocacy groups (Maine Equal Justice Partners and Consumers for Affordable Health Care), the membership organization that represents Maine’s Community Health Centers (Maine Primary Care Association), the largest federally qualified health center in Maine (Penobscot Community Health Care) and five Maine residents who will gain access to Medicaid once expansion is implemented.

The lawsuit requested that the Maine Department of Health and Human Services file a state plan amendment with the federal government within three days, and move forward with the rest of the Medicaid expansion process in an expedited fashion, so that the coverage expansion could take effect by July 2, 2018, as originally scheduled. The petitioners also filed a motion to expedite the lawsuit.

In mid-May, the LePage Administration responded to the lawsuit, arguing that they could not proceed with the implementation of Medicaid expansion until the Maine legislature allocated funding for the state’s costs associated with expansion (lawmakers did pass legislation to allocate funding, but LePage vetoed it in early July). A few days later, attorneys for Maine Equal Justice Partners countered with a filing noting that the state already had enough money to fund the first year of Medicaid expansion without having to allocate any new funds, and clarifying that the administration could not legally refuse to implement the law, regardless of the governor’s personal opposition to Medicaid expansion.

On June 4, Superior Court Justice Michaela Murphy ruled that the Maine Department of Health and Human Services had to proceed with filing a Medicaid expansion plan (a state plan amendment, or SPA) with the federal government, giving them until June 11 to do. The ruling noted that there is no cost associated with submitting an SPA to the federal government, and thus the lack of appropriation for the state’s portion of the cost of Medicaid expansion was immaterial.

Although Maine Insurance Commissioner Ricker Hamilton filed an appeal, the court order prevailed and the state did ultimately move forward with submitting the state plan amendment to the federal government in August. But Gov. LePage sent the Trump administration a strongly worded letter encouraging them to reject the state plan amendment that Maine was submitting.

Oral arguments in the court case were heard in early November, more than five months after Medicaid expansion was originally supposed to take effect. A judge ordered the LePage administration to implement Medicaid expansion by December 5, but LePage’s administration requested a stay in the order, and managed to delay the expansion of Medicaid until LePage left office.

On December 6, the judge rejected the LePage Administration’s request for a stay, but did push back the Medicaid expansion implementation deadline to February 1, 2019, albeit with retroactive coverage for people who applied since July 2018. In Judge Michaela Murphy’s decision, she noted that “the Respondent [LePage’s Administration] has persisted in hyperbolic claims of fiscal calamity, despite the uncontested factual record before the court…” In other words, the Administration’s hand-wringing about the financial crisis that Medicaid expansion would cause was unfounded in the eyes of the court. In her ruling, Murphy also clarified that once Medicaid expansion is implemented, retroactive coverage should be available to people who applied since July 2, 2018:

“The Court would emphasize that the extension of the deadline to comply should not be confused with a central holding of the prior Order. The people of Maine enacted a law that requires payment of Medicaid benefits to an expanded class of Maine citizens, and any person who meets the qualifications clearly spelled out in the Expansion Act are entitled to those benefits as of July 2, 2018.”

The case revolved around the fact that the LePage Administration said that Medicaid expansion couldn’t happen without an allocation of funds (keeping in mind that LePage vetoed the allocation of funding in the summer of 2018), while the Attorney General (who is now the Governor) and Maine Equal Justice Partners countered that the state already had adequate funding to cover the first year of Medicaid expansion costs, and additional funding could be addressed in the next legislative session. Either way, Medicaid expansion became the law — regardless of funding issues — under the terms of the ballot initiative that was approved by the voters in 2017.

I discussed the situation with the Maine People’s Alliance in June 2018, and they noted that their hope was that once the situation was resolved, expanded Medicaid coverage would be available with a retroactive effective date as early as July 2, for people who applied by that date. That’s what Judge Murphy ordered in November 2018 (expansion was to be implemented by December 5, with coverage retroactive to July 2), and again in December (expansion to be implemented by February 1, 2019, but with coverage retroactive to July 2, 2018), and it’s what ultimately happened once Medicaid was officially expanded in Maine.

Consumer advocates encouraged people to apply for MaineCare throughout 2018, on the premise that coverage could eventually be provided on a retroactive basis. Maine Equal Justice Partners confirmed in October 2018 that people were continuing to apply for MaineCare under the terms of Medicaid expansion, but were receiving rejection notices at that point. But once Mills took office and expansion took effect, coverage for the people who had already applied was retroactive as far back as July 2, 2018.

Approved 1115 waiver called for a work requirement, premiums, asset testing, and retroactive eligibility, but Gov. Mills did not implement it

Not only did LePage refuse to move forward with implementation of a legally binding ballot initiative to expand Medicaid, his administration actively worked to make the state’s existing Medicaid eligibility guidelines more stringent. Under the direction of Ricker Hamilton, whom LePage appointed to lead the state’s Department of Health and Human Services in 2017, Maine submitted an 1115 waiver, which received CMS approval in December 2018.

Several states submitted 1115 waivers to the Trump administration, seeking various changes that were never allowed under the Obama administration. But Maine’s went farther than most. The state’s waiver proposal requested a work requirement for people up to age 64, premium contributions required if household income was 51% of the poverty level or above (for a family of four at that point, that would have started at incomes of around $13,000/year), an asset test (with Medicaid only available to people with assets of under $5,000, as opposed to the current income-based eligibility system for most enrollees), and the elimination of retroactive eligibility.

Under the Trump administration, work requirements were approved for Medicaid programs in several states, although the Biden administration had revoked approval for all of them by mid-2021. Premiums and the elimination of retroactive eligibility were also approved for some states, but no state received approval to implement an asset test, and Maine’s waiver approval (granted by the Trump administration) did not give the state permission to impose an asset test (asset tests were used in some states prior to the ACA, but the ACA switched all states’ Medicaid programs to an income-based eligibility system for most enrollees; there are still asset tests for Medicaid if the person is 65 or older, or qualifying due to blindness or a disability).

Notably, Maine’s 1115 waiver would not have expanded Medicaid coverage in any way. Several states have used 1115 waivers to implement state-specific variations of Medicaid expansion, but the LePage administration instead proposed a waiver that, if implemented, would have resulted in fewer people enrolled in Maine’s Medicaid program. That was LePage’s goal all along, but Governor Mills took a different approach.

Soon after taking office, Mills notified CMS that her administration would not accept the waiver approval terms that the federal government had granted for Maine, and the waiver shows up as “withdrawn” on the CMS page that tracks 1115 waivers. Instead, Mills noted that her administration would focus on providing Medicaid enrollees with job training and workforce supports that would help them achieve employment without the threat of losing their health care coverage.

LePage reversed Maine’s pre-ACA Medicaid expansion

In addition to opposing Medicaid expansion, former Gov. LePage reversed the course on Medicaid set by his predecessor, John Baldacci, who authorized Dirigo Health in 2003. The program expanded Medicaid and subsidized private health insurance for middle-income residents. However, the program faced several financial difficulties as about 25% of the state’s residents enrolled in Medicaid by 2010 and Maine’s Medicaid spending consumed nearly 30% of the state budget. The state fell behind in Medicaid reimbursements to hospitals, which were due nearly $500 million in state and federal payments.

LePage took office in 2011 and led efforts to cut Maine’s Medicaid program. First, he reduced the eligibility limits for adults with dependents and reduced benefits for elderly Medicaid beneficiaries. Second, Maine ended coverage for adults without dependents, effective Jan. 1, 2014. The stricter eligibility limits resulted in about 25,000 people losing Medicaid eligibility. Third, the LePage administration petitioned the federal government for approval to end coverage for young adults aged 19 and 20.

When the federal government rejected the request, the administration appealed the decision in circuit court with the help of outside counsel. The state’s attorney general declined to represent the state, saying the appeal lacked merit. The 1st Circuit Court of Appeals in November 2014 upheld the federal government’s decision. The state petitioned to have the case heard by the Supreme Court, but the petition was denied in June 2015. Since the Supreme Court wouldn’t hear Maine’s case, the lower court’s decision stands, and Maine continued to provide Medicaid coverage for roughly 6,500 eligible 19 and 20-year-olds.

Footnotes

- “July 2023 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights”, Medicaid.gov, Accessed February 2024 ⤶

- ”MaineCare Expansion“, Maine DHHS, October 2023 ⤶

- ”Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2019“, U.S. Census Bureau, September 2020 ⤶

- ”Health Insurance Coverage Status and Type by Geography: 2019 and 2021“, U.S. Census Bureau, September 2022 ⤶

- ”MaineCare Renewals Data Dashboard“, Maine DHHS, February 2024 ⤶

- “Medicare Monthly Enrollment” CMS.gov, April 2023. ⤶

- “Availability of short-term health insurance in Maine” healthinsurance.org, April 7, 2023 ⤶