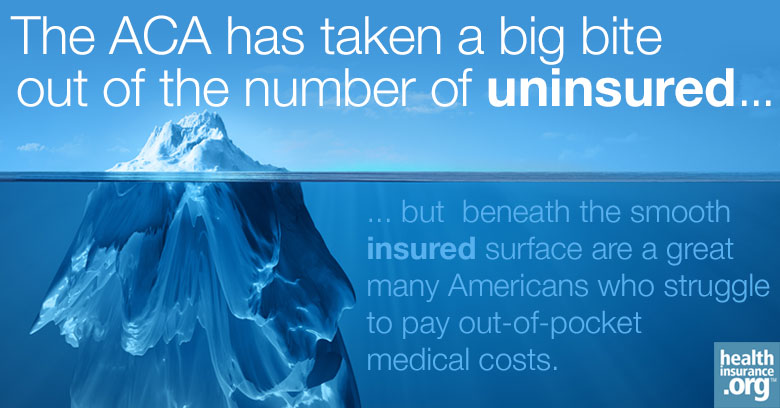

The Affordable Care Act has taken a big bite out of the ranks of the uninsured. But the underlying cost of healthcare in the United States is so high that too many Americans remain underinsured – both in employer-sponsored insurance and in the individual market. Two surveys released this week document the toll that underinsurance takes.

A Commonwealth Fund survey found that among those American adults under age 65 who were insured throughout 2014, 23 percent were underinsured – that is, their deductibles and copays were high enough to cause severe financial strain. That top line is almost unchanged since 2010; the real damage on this front was done from 2005 to 2010, when employers started shifting costs en masse to employees.

But deductibles in employer-sponsored plans do keep rising – especially for employees of small firms. In 2010, 7 percent of small-firm employees had deductibles that were more than 5 percent of their income; by 2014, 20 percent did.

Commonwealth defines as underinsured those who are exposed to out-of-pocket costs that equal 10 percent or more of household income – or 5 percent for those whose income is less than twice the federal poverty level (FPL) – and those whose deductible is 5 percent of more of family income. Half of survey respondents in this category said that they have problems paying their medical bills or said that they were paying off medical debt. That's almost an eighth of the insured adult population under 65.

Low-income insureds do a bit better

Commonwealth did find an improvement in the share of low-income people who are underinsured – from 49 percent in 2010 to 44 percent in 2012 to 42 percent in 2014. "Low-income" here means a household income under 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL).

Commonwealth locates the drop mainly among Medicaid beneficiaries. Going forward, relatively robust insurance available to low-income buyers of private plans on the exchanges established by the ACA may also be a factor. A Kaiser Family Foundation survey of those who purchased health insurance on the individual market indicates that low-income buyers' inherent disadvantage is partially offset by the ACA's sliding subsidy structure, which reduces out-of-pocket costs as well as premiums for lower income buyers.

Overall, the Kaiser survey, conducted in early 2015, found that 85 percent of those who bought ACA-compliant plans rate their plans as "good," "very good" or "excellent." That's lower than the approval rate for employer-sponsored plans, but it does indicate a solid baseline of satisfaction.

When we come to measures of underinsurance, the picture is more mixed. Among those with ACA-compliant plans (including those sold off-exchange), 38 percent say that they still feel vulnerable to high medical bills. Fifty-seven percent say that they feel well-protected by their plans.

The uneasiness extends both to premiums and out-of-pocket expenses. Among those in ACA-compliant plans, 31 percent say it is somewhat difficult to pay the monthly premium, and 15 percent say it is very difficult. Sixteen percent say they have had problems paying medical bills, and 18 percent that they did not fill a prescription because of the cost.

Kaiser respondents with higher deductible plans are more likely than those with lower deductibles to say they feel vulnerable to high medical bills, 55 percent to 22 percent. But in the individual market, those with high-deductible plans have higher incomes on average – the reverse of the situation in employer-sponsored insurance. They therefore are about equally likely to report problems paying medical bills as those in low-deductible plans. The vulnerability – too high across the board – is evenly spread. Why is that?

A little-known subsidy goes a long way

Shoppers on ACA exchanges with incomes under 200 percent FPL are eligible for Cost Sharing Reduction subsidies (CSR) in addition to premium subsidies – albeit only if they buy Silver-level plans instead of the cheapest Bronze level (or more expensive Gold or Platinum). CSR vastly reduces deductibles and out-of-pocket costs for those under 200 percent FPL (and much more weakly for those in the 200-250 percent FPL range). A CSR-enhanced silver plan pays 94 percent of the average user's yearly out-of-pocket costs for buyers under 150 percent FPL and 88 percent of those costs for buyers between 150 and 200 percent FPL. That's better coverage than most employer-sponsored plans offer.

Kaiser's respondents self-report their deductibles to be lower at lower income levels. Among those below 138 percent FPL, 14 percent report themselves to be in a high-deductible plan – defined by Kaiser as more than $1,500 per individual – versus 44 percent in low deductible plans. Among those with incomes between 138 and 250 percent FPL, the split is nearly even: 23 percent high, 24 percent low (many in each category are unsure). The percentage of those with high-deductible plans rises with each step up in income bracket.

It's unfortunate that Kaiser does not provide a figure on this question for buyers with incomes below 200 percent FPL, because that is the level at which CSR tapers off abruptly. My own analysis of HHS enrollment figures indicates that over 80 percent of buyers on the federal exchange with incomes under 200 percent FPL buy Silver plans and so access CSR – but Silver plan takeup falls off abruptly above that 200 percent threshold. Though Kaiser lumps the 200-250 percent FPL cohort together with those at a lower level, its numbers still indicate that CSR is providing significant protection against underinsurance to lower income buyers.

Strapped Americans stretched thin

Not enough, though. Taken together, Kaiser and Commonwealth show that large numbers of insured Americans in all forms of insurance – Medicaid and disability Medicare as well as private and employer-sponsored insurance – suffer severe financial harm and forego needed medical care because they are underinsured.

Compounding the problem of underinsurance is the overall financial precariousness of American households. Kaiser asked respondents what they would do if they were faced with an unexpected medical bill of $500 or $1500 that insurance did not cover (as Americans all too frequently are).

Only 44 percent overall said that they would pay the $500 bill without borrowing; only 26 percent could manage to do so for the $1,500 bill. Those results jibe with a survey recently conducted by Bankrate, which found that only 38 percent of Americans would pay for a $500 or $1000 emergency out of savings.

The ACA has dramatically cut the ranks of the uninsured – to 11.9 percent of the population, down from 18 percent in mid-2013, according to Gallup. For buyers with incomes under 200 percent FPL in the individual market – who constitute 68 percent of all buyers on HealthCare.gov – Cost Sharing Reduction reduces the risk of underinsurance for most. But many buyers at higher income levels – and a significant minority below 200 percent FPL – do face very high deductibles and copays.

The ACA has improved Americans' access to affordable healthcare. But we have a long way to go.

Postscript

A third study released this week, from the Urban Institute, finds that 9.4 million fewer Americans are having trouble medical bills as of the first quarter of 2015 than in the first quarter of 2013, prior to the ACA launch.

But the study does not differentiate between those who have trouble paying bills because they are uninsured and those who have trouble because they are underinsured, nor does it speculate as to the causes of the drop.

Andrew Sprung is a freelance writer who blogs about politics and policy, particularly health care policy, at xpostfactoid. His articles about the rollout of the Affordable Care Act have appeared in The Atlantic and The New Republic. He is the winner of the National Institute of Health Care Management’s 2016 Digital Media Award.