Most of the discussion swirling around the current ACA repeal battle focuses on how the legislation would impact people who have Medicaid or who get their health insurance in the individual market. But nearly half the U.S. population has health insurance through an employer-sponsored plan – and the repeal proposals would affect them as well.

In this post, I'll address specifically potential impacts to people who have employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) that's deemed small-group coverage. (In most states, "small-group" means a business with up to 50 employees, although four states – California, Colorado, New York, and Vermont – consider businesses with up to 100 employees to be small groups.)

If you're one of 17 million Americans who gets job-sponsored health insurance through a small-group plan – or if you're an employer who's offering the plan – you may have reasons to be concerned about how your coverage would change under GOP proposals in either the House or Senate legislation.

What could end up un-covered

If your employer signed up for a small-group plan in 2014 or later, the coverage is compliant with the law's many provisions – including the ACA's essential health benefits – just like plans in the individual market.

But under both the Senate and House versions of repeal legislation, states could utilize waivers to redefine essential health benefits for plans sold within the state. That means health plans compliant with the new law – including small-group plans – would not be required to cover the full suite of benefits currently mandated by the ACA.

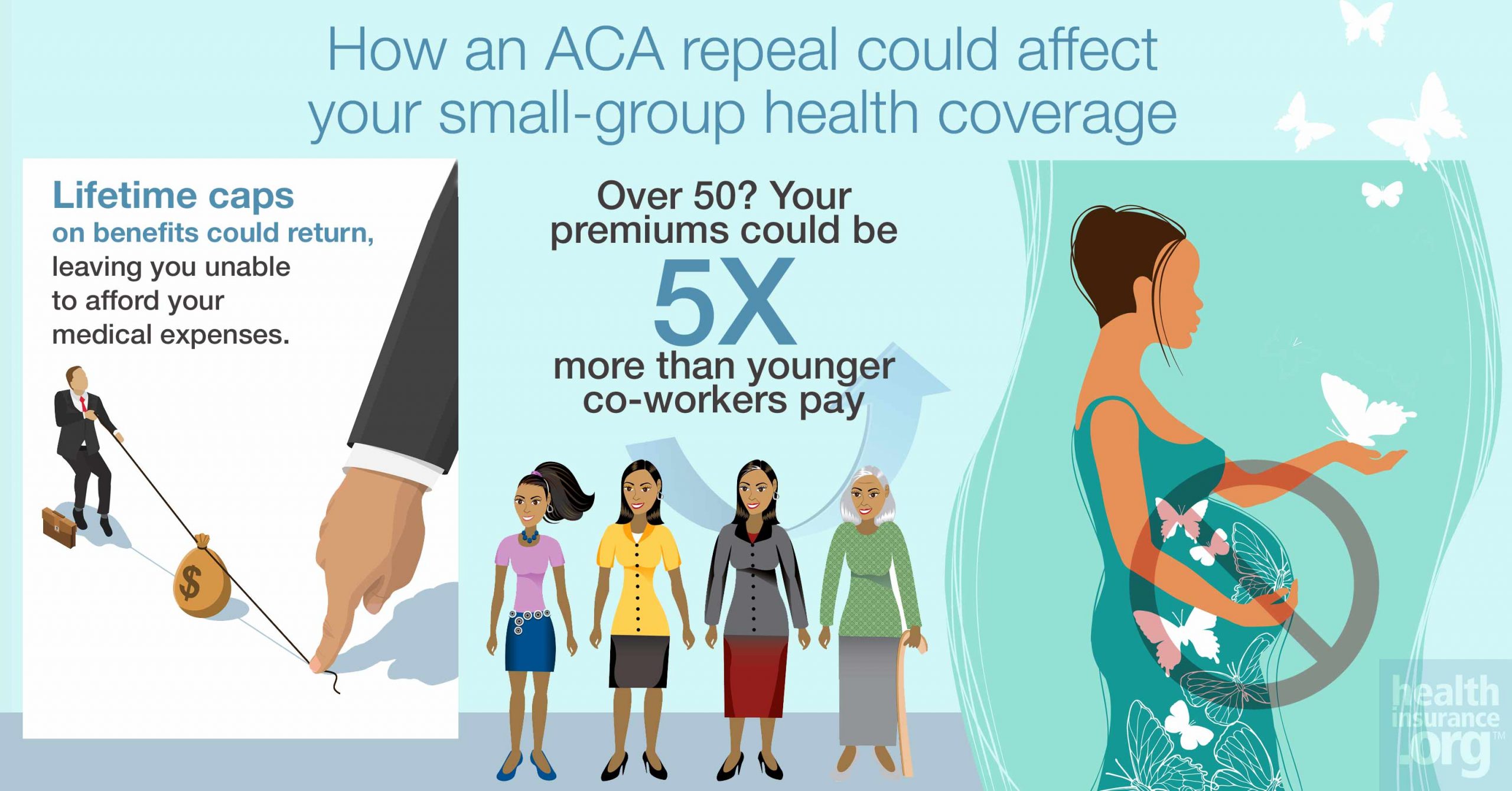

It's also important to note that the ACA's ban on lifetime and annual benefit caps, and the law's cap on annual out-of-pocket costs, only apply to in-network care that's considered an essential health benefit. So even if repeal legislation doesn't directly roll back those ACA consumer protections, they would be weakened in states that opt for a waiver to redefine essential health benefits.

Here are just a couple of examples of how redefined EHBs might hurt folks in small-group plans:

Prescription drug coverage

Prior to the ACA, there were no federal regulations requiring individual and small-group plans to cover prescription drugs. Most plans did, but there was a growing trend towards less robust drug coverage (for example, plans that only covered generic drugs) in the years leading up to the ACA. Spending growth on prescription drugs has outpaced overall medical cost growth, and an Avelere analysis found that prescription spending accounted for 17.5 percent of rate increase justifications in 2016.

Since prescriptions are a significant cost driver – and likely to remain that way as more high-cost specialty drugs are developed – insurers will jump at the opportunity to offer plans that don't cover all types of prescription drugs. Under the ACA, individual and small-group plans have to cover at least one drug in every US Pharmacopeia category and class, or as many drugs in each category and class as the benchmark plan in the state, whichever is greater. If a state is allowed to redefine essential health benefits and doesn't include prescription coverage (or, perhaps, includes a less robust standard, such as allowing insurers to offer plans without coverage for specialty drugs), people who need high-cost drugs could quickly face unaffordable medical costs.

In 2015, there were no multiple sclerosis drugs that cost less than $50,000 per year. And those prices have continued to increase since then. Some states have taken action to limit patients' out-of-pocket exposure for specialty drugs (and these are presumably states that would not seek to redefine essential health benefits to make coverage less comprehensive). But by and large, the only thing protecting patients with conditions like MS is the fact that the ACA caps annual out-of-pocket spending on essential health benefits, and includes prescription coverage as an essential health benefit.

If a state were to redefine essential health benefits, people with small-group coverage could find themselves out of luck if they end up needing high-cost prescriptions. The medications may not be covered at all, or they could have open-ended coinsurance with no cap on out-of-pocket costs.

Maternity coverage

Maternity care is another one of the ACA's essential health benefits, which means that it's currently covered on all ACA-compliant small group plans. There has been significant concern that maternity coverage could all but disappear in the individual market in states where essential health benefits are redefined via a waiver, as coverage would likely revert back to the way it was pre-ACA, when just 12 percent of individual market plans covered maternity care.

People with small group coverage are a bit more protected but it depends on where they live and how many coworkers they have. Employer-sponsored plans are required to cover maternity if the employer has 15 or more employees, under a federal law that's been in place since 1978. And there were 15 states that required all small-group plans (even when the business had fewer than 15 employees) to cover maternity care pre-ACA.

But if you work for a small business that has fewer than 15 employees, your access to maternity coverage could be on shaky ground if your state doesn't mandate coverage. The vast majority of small businesses have fewer than 10 employees. These are the businesses that are least likely to offer small-group coverage, but if they do, access to maternity care would be limited in states that redefine essential health benefits and don't include maternity. (And it's worth noting that in those states, maternity coverage in the individual market could disappear altogether, making it impossible for workers at small firms to obtain maternity coverage if their small group plan no longer included it.)

Older employees would pay more

Under the Affordable Care Act, insurers cannot use a small group's medical history to set rates for ACA-compliant plans. As is the case in the individual health insurance market, rates in the small-group market can only vary based on family size, tobacco use (with a ratio of no more than 1.5 to 1), and age (with a ratio of no more than 3 to 1 for older adults versus younger adults).

Some states already had rules like this prior to the ACA, although 38 states and DC still allowed small-group premiums to be based on medical history as of 2013. This was no longer allowed for new plans in any state as of 2014, thanks to the ACA.

Under both the House and Senate proposals, small groups would still be able to obtain coverage without regard for the overall medical history of the group's members. However, both bills set the default age rating ratio for older insureds to 5:1, although it could be even higher than that if a state opted for a different ratio. The result is that older employees could be charged at least five times as much as younger employees.

Tax credits

If your employer does offer small-group coverage, they may be taking advantage of the Small Business Health Care Tax Credit, a provision of the ACA. The credit is only for businesses that purchase coverage through the SHOP exchange. (Eligibility for the tax credit only lasts for two years, and depends on the number of employees, their average wages, and the employer's contribution to the premiums.)

That credit – though not widely used – would be eliminated starting 2020 by both the House and Senate bills.

Employer mandate

Under repeal, the employer mandate penalty would be eliminated, but in terms of small groups, it would affect only employers with exactly 50 employees (and employers with 51 to 100 employees in California, Colorado, New York, and Vermont), since small groups with up to 49 employees have never been subject to the mandate. (One exception: Since 1974, Hawaii has required most employers to offer coverage to any employee who works more than 20 hours per week.)

Small-group coverage isn't immune to repeal

The future of the Affordable Care Act is very uncertain, and we don't yet know what changes Congress might eventually end up making, since moderates and conservatives seem to be unable to compromise for now.

Some of the most egregious changes under each version of the bill – cutting federal funding for Medicaid, reducing premium tax credits, and eliminating cost-sharing subsidies – would not apply to people who get their coverage via a small-group plan. But the option for states to use waivers to adjust essential health benefit requirements would clearly impact the quality and affordability of small-group plans.

In states that opt to redefine essential health benefits, comprehensive plans will be harder to find and more expensive, while less robust coverage could become the norm. And consumer protections that we've come to expect, including caps on out-of-pocket spending and bans on annual and lifetime benefit limits, could be eroded.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.