Health insurance Marketplaces by state

States vary in terms of how they manage their insurance markets and health insurance exchanges. Here’s what you need to know.

Advance Premium Tax Credit (APTC) Repayment and Refund Calculator

HIO developed this calculator in 2024, using the IRS guidance about the premium tax credit and ATPC, as well as IRS Form 8962 (2023).

This calculator is for educational and illustrative purposes only and should not be construed as financial or tax advice. It uses the income and other information you provide. Contact a trusted professional advisor or accountant about any specific requirements or concerns.

Click calculate to see updated repayment/refund

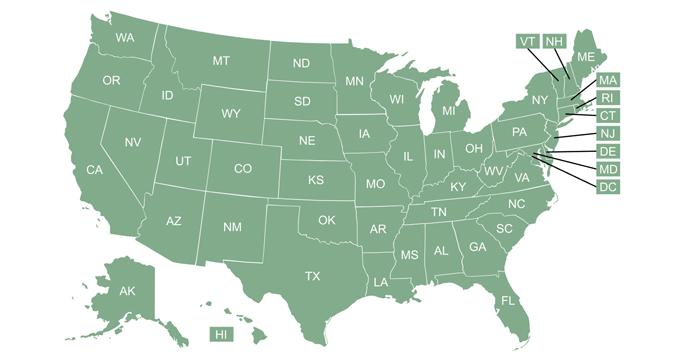

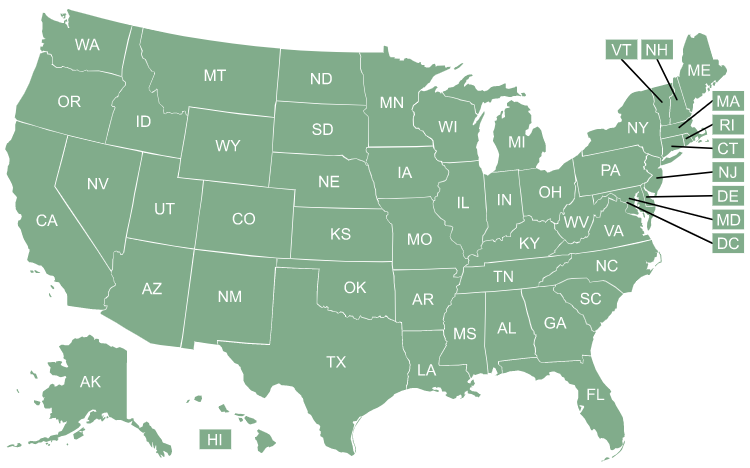

Health insurance Marketplaces vary by state

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), enacted in March 2010, called for the creation of an exchange in each state, but the practical implementation of those exchanges varies considerably from one state to another.

This overview answers questions about what the exchanges are, what they offer, and how they work. You can select a state on the map below to see specific details about that state’s exchange.

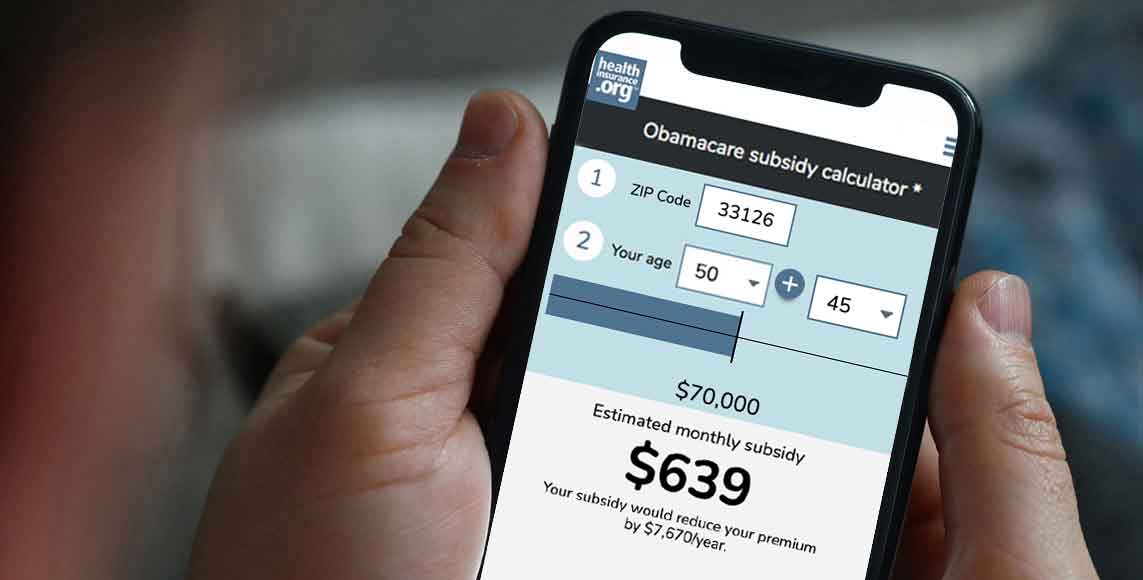

How much could you save on 2024 coverage?

Compare health plans and check subsidy savings.

What is a health insurance Marketplace?

A health insurance Marketplace – also known as a health insurance exchange – is a place where consumers in the United States can purchase ACA-compliant individual/family health insurance plans and receive income-based subsidies to make coverage and care more affordable. As of early 2023, there were nearly 15.7 million people enrolled in Marketplace plans throughout the country.1

Each state has just one official Marketplace, operated either by the state, the federal government, or both. In most states, HealthCare.gov serves as the enrollment platform and runs the customer service call center. But some states run their own platforms, such as Covered California, New York State of Health, Connect for Health Colorado, and MNsure.

More frequently asked questions about health insurance Marketplaces

Do I have to buy my health insurance through a Marketplace?

You are not required to buy coverage through the Marketplace. There is no longer a federal penalty for not having health coverage (although DC and four states have state-based penalties for people who choose to remain uninsured). And even when there was a federal penalty, people could choose to purchase their coverage off-exchange instead of buying a plan through the Marketplace (with the exception of DC, where individual and small-group coverage is only available through the Marketplace).

But if you don’t buy your coverage through the exchange, you cannot obtain premium tax credits or cost-sharing reductions, even if you’d otherwise be eligible for them (and most people are eligible for subsidies). This is one of the primary reasons people shop in the Marketplace, as full-price individual health insurance premiums would simply be too costly for most people.

How do health insurance Marketplaces help consumers?

In each state, the health insurance Marketplace allows consumers to select from among a variety of private health insurance companies that offer different qualified health plans. (In some areas of the United States, only one insurer offers medical plans for sale in the Marketplace, but there will still be a variety of plan options available).

All qualified plans offered for sale in the Marketplace must be ACA-compliant – meeting standards established and enforced by the federal and state governments. So when a person shops in the health insurance Marketplace, they can be sure that the participating insurers will not use medical underwriting or exclude pre-existing conditions. All of the available plans will cover the ACA’s essential health benefits without annual or lifetime benefit caps.

Income-based premium subsidies and cost-sharing reductions are only available through the health insurance Marketplace, and are a key aspect of keeping health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket costs affordable for lower-income and middle-class Americans.

Who’s eligible to use the health insurance Marketplaces?

With the exception of people who are enrolled in Medicare coverage, virtually all Americans are eligible to use the health insurance Marketplace as long as they’re lawfully present in the U.S. (Note that DACA recipients cannot use the Marketplace, despite being lawfully present, although the Biden administration has proposed a rule change that is expected to allow DACA recipients to use the Marketplace to enroll in coverage for 2024 and future years.)

But practically speaking, the Marketplaces were designed to provide coverage for individuals and families who were either uninsured or already buying their own health insurance. This includes people who are self-employed, people who are employed by a small business that doesn’t offer health benefits, and people who have retired before age 65 and are thus too young to be covered by Medicare.

The majority of non-elderly Americans get their coverage from an employer, which means they don’t need to use the Marketplace. They can choose to decline their employer’s coverage and select a plan in the Marketplace instead, but they won’t be eligible for financial assistance unless the employer’s coverage wouldn’t be considered affordable and/or wouldn’t provide minimum value.

Most non-elderly Americans who are eligible for Medicaid can use the Marketplace to enroll in Medicaid, or at least to determine their eligibility for Medicaid. In some states, the Medicaid enrollment process is completed via the Marketplace, while in other states, the Marketplace sends the consumer’s information to the state Medicaid agency to finalize the eligibility and/or enrollment process.

What are the types of health insurance marketplaces?

A state’s health insurance marketplace can be run by the state, by the federal government, or both. As of the 2024 plan year :

- DC and 18 states have fully state-run marketplaces, which means they oversee the marketplace and operate their own website and call center (examples are GetCoveredNJ, Pennie, Vermont Health Connect, Washington Healthplanfinder, etc.).

- Twenty-three states rely fully on the federal government for their marketplaces. They use the HealthCare.gov website and customer service call center.

- Three states (Arkansas, Oregon, and Georgia) have state-based marketplaces that use the federal platform (SBM-FP), which means they oversee their own marketplace but rely on HealthCare.gov for enrollment.

- Six states have state-federal partnership marketplaces, which are similar to the states that rely fully on the federally-run marketplace, but involve more state participation in oversight and management (all of these states use HealthCare.gov for enrollment).

You can find more information here about the types of health insurance Marketplaces, how they work, which model each state uses, and how states’ approaches to this have changed over time.

When can consumers buy health insurance through their marketplace?

There is an open enrollment period each fall when people can enroll in coverage through the Marketplace or change their coverage for the coming year (the same open enrollment window also applies to plans that are available outside the Marketplace, purchased directly from the insurance companies).

In most states, the open enrollment period is November 1 to January 15, with coverage effective either January 1 or February 1, depending on when the person enrolls. But there are some state-run exchanges that have different deadlines.

Outside of the annual open enrollment period, a special enrollment period is necessary in order to enroll in a plan through the health insurance Marketplace (or outside the Marketplace, directly through an insurer) or change to a different plan. Special enrollment periods are triggered by a variety of qualifying life events, and will give you at least 60 days to select a new medical plan.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.

Footnotes

- ”Effectuated Enrollment: Early 2023 Snapshot and Full Year 2022 Average” CMS.org, March 15, 2023 ⤶