Federal short-term health plan rules: Key takeaways

- Federal rules allows 364-day plans, with option to renew for up to 36 months.

- A federal judge upheld the Trump administration’s new rule in a 2019 ruling.

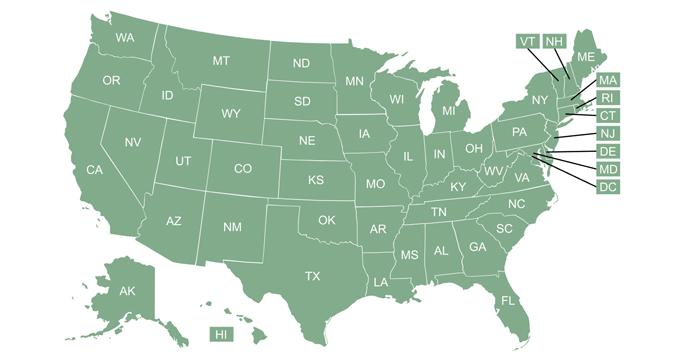

- More than half the states have stricter regulations, and there are 11 states where no short-term plans are available.

- Recent state-based legislation pertaining to short-term plans: Some have tightened state regulations and others have relaxed them.

- How many people are expected to switch to short-term plans?

Millions of Americans seeking alternatives to the Affordable Care Act’s comprehensive (but in some cases cost-prohibitive) health coverage may gravitate to short-term health plans, enticed by an attractive feature: coverage that they can hold on to longer.

Thanks to an executive order signed by President Donald Trump and the associated regulation changes that HHS finalized in August 2018, individual plan buyers who are unable – or unwilling – to buy ACA-compliant plans may now have the option to purchase a short-term health insurance plan with an initial duration of nearly a year and renewal options that allow the plan to remain in force for three years.

The 2018 rule that extends the allowable duration of short-term plans was upheld by a federal district court judge in 2019, and again upheld by an appeals court, in a 2-1 ruling issued in July 2020.

But the availability of short-term health insurance plans varies from one area to another. Some states have much tighter restrictions on short-term plans, and insurers choose to offer different plans in different areas.

2018 rule reverts to the previous definition of “short-term” and allows renewal for up to 36 months; Rule is upheld by a federal judge in 2019 and an appeals court panel in 2020

Prior to 2017, long-standing federal regulations had limited the duration of short-term health plans to 364 days, though some states had capped duration at six months and others had regulations that didn’t allow for short-term plans at all. Short-term plans have always been exempt from ACA rules, but Obama Administration regulations that took effect in 2017 limited short-term plans to 90 days.

Prior to 2017, long-standing federal regulations had limited the duration of short-term health plans to 364 days, though some states had capped duration at six months and others had regulations that didn’t allow for short-term plans at all. Short-term plans have always been exempt from ACA rules, but Obama Administration regulations that took effect in 2017 limited short-term plans to 90 days.

In October 2017, President Trump signed an executive order directing federal agencies to draft regulations aimed at rolling back those restrictions on short-term plans. In February 2018, HHS proposed new rules for short-term plans. They accepted comments on the proposed rule until April 23, 2018, and about 12,000 comments were submitted. The final rule was issued in early August, and took effect on October 2, 2018.

In September 2018, a group of seven plaintiffs (representing health insurers, physicians, and consumer advocacy organizations) sued the Trump administration, arguing that the new rules are contrary to HIPAA, and arbitrary and capricious. In July 2019, however, U.S. District Court Judge Richard J. Leon ruled in favor of the Trump administration. In his ruling, Leon expressed his opinion that Congress had intentionally left the definition of “short-term limited duration insurance” up to HHS (as opposed to defining it themselves) and that the Trump administration had not overstepped with the 2018 regulations that significantly expand short-term health plans.

The ruling was appealed, but an appeals court panel upheld it in July 2020 with a 2-1 ruling in favor of the Trump administration’s extension of the allowable duration of short-term plans.

The final rule does three things:

- Allows short-term plans to be sold with initial terms of up to 364 days.

- Allows short-term plans to be renewed as long as the total duration of the plan doesn’t exceed 36 months.

- Requires short-term plan information to include a disclosure to help people understand how short-term plans differ from individual health insurance.

The new rule reverts to the previous definition of “short-term.” A plan is considered “short-term” as long as it has an initial term of less than a year (ie, no more than 364 days). But HHS is also allowing short-term plans to offer enrollees the option to renew their plans without additional medical underwriting and use renewal to keep the same plan in force for up to 36 months (plans with renewability options may be more attractive to consumers, but they’re also generally more expensive than a non-renewable short-term plan).

HHS justified this by noting that the coverage has long been called “short-term limited duration” health coverage, and pointing out that “short-term” and “limited duration” must mean different things, otherwise it would be a redundant name. So they’re saying that “short-term” refers to the initial term, which must be under 12 months. But they’re allowing the “limited duration” part to mean up to 36 months in total, under the same plan. It’s important to note that HHS clearly expected this to be challenged in court, as they included a severability clause for the part about 36-month total duration: If a court ever strikes down that provision, the rest of the rule would remain in place (a lawsuit was filed over the legality of the new short-term insurance rule in September 2018, but that case ended with a ruling in favor of the Trump administration).

In the final rule, HHS noted that there is nothing in federal statute that would prevent a person from enrolling in a new short-term plan after the 36 months (or purchasing an option from the initial insurer that will allow them to buy a new plan at a later date, with the new plan allowed to start after the full 36-month duration of the prior plan). So technically, federal rules allow people to string together multiple “short-term” plans indefinitely. But there are quite a few states with much stronger short-term plan regulations, and some states have implemented new restrictions on short-term plans specifically in response to the new federal rules.

The disclosure notice required in the final rule is intended to inform consumers of several aspects of short-term coverage: That the plans are not required to comply with the ACA, may not cover certain medical costs, and may impose annual/lifetime benefit limits. The disclosure also notes that the termination of a short-term plan does not trigger a special enrollment period in the individual market (although it does for group health plans; see page 51 of the final rule), and thus enrollees who develop health conditions while covered under a short-term plan — and thus aren’t eligible to buy another short-term plan — might find themselves uninsured and having to wait until the next open enrollment period to sign up for coverage.

The disclosure notice adopted in the final rule is more comprehensive than it was in the proposed rule, and includes specific examples of the services that might not be covered by short-term plans “such as hospitalization, emergency services, maternity care, preventive care, prescription drugs, and mental health and substance use disorder services.” HHS notes that there is little evidence for short-term plans excluding hospitalization or emergency services, but it’s fairly common to see short-term plans that don’t cover preventive care, maternity care, outpatient prescriptions, or mental health/substance use treatment.

HHS made it clear in the final regulations that states may continue to implement more restrictive rules, just as they did prior to 2017 (states cannot implement rules that are more lenient than the new federal regulations). A few states – New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont – already didn’t have short-term plans at all, generally due to state mandates and regulations that make it unprofitable for insurers to offer short-term plans. And as of 2020, four additional states — California, Colorado, New Mexico, Maine, and Hawaii — have joined them, with no insurers offering short-term plans (in California, state law prohibits the sale of short-term plans as of 2019; in Hawaii, Colorado, Maine, and New Mexico, new state laws are restrictive enough that insurers have opted not to offer short-term plans for the time being). In Washington, short-term health plans were not available for several months in late 2018/early 2019, but sales resumed once the plans were modified to meet the state’s new requirements.

In addition, several states already capped short-term plans at three or six months in duration, even before the Obama administration took action to limit short-term plans to three months, and others have subsequently implemented three- or six-month caps on short-term plans. (Use this map to see more details about how it regulates short-term plans in your state). Ultimately, there are more states with their own restrictions on short-term plans than there are states that are defaulting to the federal rules.

States are still allowed to limit short-term plans as they see fit, and in all areas of short-term plan regulation other than the three provisions of the final rule, HHS notes that it’s up to each state to set rules applicable to short-term plans sold within the state.

New state-based legislation & regulations aimed at changing the limits that apply to short-term plans

Since the Trump administration proposed the new rules, several states have taken action to restrict the sale of short-term plans, with varying degrees of success:

- California enacted a bill in 2018 (SB910) that prohibits the sale of short-term plans in the state as of January 1, 2019. The legislation was supported by the California Department of Insurance, and by Kaiser and Blue Shield of California. Anthem Blue Cross, however, opposed the measure.

- Hawaii lawmakers passed HB1520, and Governor Ige signed it into law in July 2018. The legislation prohibits the sale of a short-term plan to anyone who was eligible to purchase a plan in the exchange during the previous calendar year, either during open enrollment or during a special enrollment period. The only people who aren’t eligible to purchase coverage in the exchange are undocumented immigrants, incarcerated individuals, and people who are eligible for premium-free Medicare Part A. So HB1520 essentially eliminates the short-term market in Hawaii, as virtually everyone is eligible to purchase coverage in the exchange in any given calendar year. As of October 2018, there were no longer any insurers offering short-term plans in Hawaii.

- Maryland enacted HB1782 in 2018, which limits short-term plans to three months and prohibits renewal.

- Vermont also enacted legislation to limit short-term plans to three months and prohibit renewal, but Vermont already had no short-term plans for sale.

- Lawmakers in Illinois considered legislation (HB1337 HA1, as amended by the House) to limit short-term plans to three months, and prevent renewals. But that limit was considered politically infeasible, so lawmakers instead focused on HB2624, which passed in the legislature and was sent to the governor in late June. The amended version of HB2624 limits short-term plans to durations of less than 181 days, prohibits renewals, and prevents an enrollee from purchasing a new short-term plan from the same issuer within 60 days of the termination of a previous short-term plan. Governor Rauner vetoed HB2624, but lawmakers overrode his veto in November 2018 and the bill became law.

- Washington‘s insurance commissioner, Mike Kriedler, who has called short-term plans “a poor solution for consumers,” announced in March 2018 that his office would begin the process of rule-making to define short-term plans at the state level, in response to the federal government’s proposal to expand the definition of short-term plans. An outline of the proposed regulations was published in June 2018. It was finalized in October 2018, and took effect in January 2019. The new rules limit short-term plans to three-months, prevent renewal, and prohibit insurers from selling short-term plans to anyone who had already had three months of short-term coverage in the prior 12 months. The new rules also prohibit the sale of short-term plans during open enrollment, if the short-term coverage is to take effect in the coming year (ie, they can’t be sold in direct competition with ACA-compliant plans during open enrollment). The only insurer that had been selling short-term plans in Washington suspended sales in November 2019 due to the new regulations. Sales resumed in April 2019, although the plans could not be purchased between November 1 and December 15, 2019 if they had a January 2020 effective date.

- Colorado implemented rules in 2019 that are restrictive enough that there are no longer any insurers willing to offer short-term plans in the state.

- Delaware and New Mexico have both implemented regulations that limit short-term plans to three-month durations and prohibit renewals. There are still short-term plans for sale in Delaware, although it appeared that none were for sale in New Mexico as of mid-2019.

- Maine enacted legislation (LD1260) that requires short-term plans (starting in 2020) to terminate no later than December 31 of the year in which they’re issued. The new law also imposes various other requirements, including a requirement that all short-term plans be sold via in-person meetings (ie, no online or phone sales), and a ban on the sale of short-term plans during the ACA’s open enrollment period (unless the plan is slated to start and end prior to the start of the new year). As of 2020, there are no longer any insurers offering short-term plans in Maine.

But other states have worked to expand access to short-term plans, including:

- Indiana enacted legislation (HB1631) in 2019 that allows short-term plan durations to align with the new federal rules (ie, up to 364-day terms, and total duration of up to 36 months, including renewals). The legislation also added a new requirement that short-term plans have benefit maximums of at least $2 million, and took effect in July 2019.

- Oklahoma also enacted legislation (SB993) in 2019 that allows short-term plans to have maximum durations in line with the federal rules, starting in November 2019 (prior to that, Oklahoma’s regulations limit short-term plans to six months and prohibit renewals).

- Arizona has also enacted legislation (SB1109) in 2019 to allow short-term plans to have maximum durations in line with federal rules. This change took effect in late August 2019.

- Missouri lawmakers considered HB1685 (it passed the House in 2018, but not the Senate), which would have defined short-term coverage as a policy with a duration of less than one year. The House passed the bill, but it didn’t reach a full vote on the Senate floor. Missouri regulations currently limit short-term plans to no more than six months in duration.

- In Minnesota, current rules restrict short-term plans to no more than 185 days in duration, and residents are limited to having short-term insurance for no more than 365 days out of a 555-day period. But HF3138 would have redefined a short-term plan as being less than a year in duration and eliminated the 365 out of 555 days cap. The bill passed the House, but did not advance to a vote on the Senate floor.

- In Virginia, lawmakers passed SB844 in 2018 and SB1240 in 2019, both of which would have relaxed the state’s rules for short-term plans. But Governor Northam vetoed both bills (Virginia’s newly-blue legislature is considering legislation in 2020 that would sharply limit short-term plans).

So states are taking varying approaches on short-term plans, with some clearly wanting to expand access, while others prefer to restrict or eliminate short-term plans in an effort to protect their ACA-compliant markets.

Short-term plans are not considered individual market coverage under federal rules, so they are not subject to the ACA’s regulations. That means there is a long list of things that they can do to make coverage less expensive than regular individual market plans, including the use of medical underwriting (pre-existing conditions aren’t covered, and applicants can be rejected based on their medical history), annual and lifetime benefit caps, and coverage that doesn’t include the ACA’s essential health benefits.

States can require short-term plans to adhere to state regulations that apply to the individual market, and some states have done so.

Current state regulations: More than half the states restrict initial terms and/or total duration of short-term plans

As it stands now, several states limit short-term plans to six months or less:

- Delaware limits plans to three months

- District of Columbia (three months, no renewals)

- Illinois

- Louisiana (limited to six months only if the insurer looks back more than 12 months to determine pre-existing conditions)

- Maryland enacted legislation in 2018 to limit STLDI plans to three months

- Michigan (185 days)

- Minnesota (185 days; legislation to extend this failed in 2018)

- Missouri (legislation to extend short-term plans failed in 2018)

- Nevada (185 days)

- New Hampshire

- North Dakota (185 days)

- Oregon (90 days)

- South Dakota (policies lasting longer than six months are required to be guaranteed renewable, which effectively limits the short-term market to plans with durations of six months or less)

- Vermont (three months, effective May 2018 — but Vermont does not have any short-term plans available as of 2018).

- Washington limits short-term plans to three months

A handful of states allow short-term plans to have initial terms in line with the new federal rules (ie, up to 364 days, or close to it), but place more restrictive limits on renewals and total plan duration:

- Idaho (renewals required if the plan is an “enhanced” short-term plan; non-enhanced short-term plans are limited to six months)

- Kansas (only one renewal permitted)

- Ohio (renewals not permitted)

- South Carolina (11-month maximum initial term, and 33-month maximum duration)

- Utah (363-day maximum initial term, and renewals are not permitted)

- Wisconsin (total duration limited to 18 months)

- California

- Colorado (plans are technically allowed, but with significant restrictions; the state’s remaining short-term insurers stopped offering plans as of 2019)

- Connecticut

- Hawaii limits plans to three months, but no insurers offer plans now that the state’s new rules are in effect.

- Maine (new rules took effect in 2020, and no insurers have filed 2020 plans under the new rules.)

- New York

- New Jersey

- Massachusetts

- New Mexico (state regulations limit the plans to three months and prohibit renewals, but no insurers are offering plans as of mid-2019)

- Rhode Island

- Vermont (there are no short-term plans available in Vermont, but legislation was also enacted in 2018 to limit short-term plans to three months and prohibit renewals, in case any plans are approved in the future)

How many people will switch to short-term plans?

HHS projected that 500,000 people would shift from individual market plans to short-term plans in 2019 as a result of the new federal rules for short-term plans. They estimated that 200,000 of those people had on-exchange plans in 2018, and 300,000 had off-exchange plans. They estimated that another 100,000 people who were uninsured in 2018 would enroll in short-term plans in 2019 as a result of the new regulations. So for 2019, HHS projected a total increase of 600,000 people covered under short-term health plans.

And by 2028, they expect the total increase in the short-term insurance population to reach 1.4 million, while the individual insurance market population is expected to decline by 1.3 million over that time.

But it’s difficult to know how all of the moving parts will affect the eventual outcome. Short-term plans existed before the ACA, but the individual market plans sold in most states were subject to medical underwriting that was similar to short-term plans. (That’s very different now, since individual market plans are no longer medically underwritten.)

And the ACA’s individual mandate penalty was in place from 2014 through 2018, likely suppressing enrollment in short-term plans. People who relied on short-term plans during those years were subject to a penalty under the ACA’s individual mandate if they were not otherwise exempt from it, because short-term plans are not considered minimum essential coverage. But the individual mandate penalty no longer exists, as it was repealed starting in 2019 under the GOP tax bill that was enacted in late 2017.

In addition, premiums have risen considerably in the individual market since 2016. For both 2017 and 2018, there were large double-digit average rate hikes for ACA-compliant plans. (For 2018, a significant portion of the rate increase was on silver plans, due to the Trump Administration’s decision to eliminate funding for cost-sharing reductions, but the rate hikes on plans at other metal levels was still considerable in many areas.). Rate hikes were much more modest for 2019 and 2020, even decreasing in some areas. But for people who were already facing unaffordable premiums in 2018, anything short of a sharp premium decrease means that coverage is likely still unaffordable (that’s assuming the person isn’t eligible for premium subsidies, and has to pay the entire premium themselves).

Premiums increase in the short-term market as well, to keep up with medical inflation. But since short-term plans don’t cover pre-existing conditions and can reject applicants based on medical history, their overall pool of insureds is much healthier than the general individual market. So the premium increases in the short-term market have been much more modest than the increases in the individual market.

With the sharply lower premiums, and now that there’s no longer an individual mandate penalty in most states, short-term plans might be especially attractive to people who aren’t eligible for premium subsidies in the exchange. HHS has noted that the number of people with unsubsidized individual market coverage (including everyone enrolled off-exchange) dropped by 20 percent from 2016 to 2017. These people may be uninsured, they may have obtained employer-sponsored coverage, or they may have joined a health care sharing ministry – but they were no longer in the individual market as of 2017. And for people who don’t qualify for premium subsidies, premiums in the individual market are higher now than they were in 2017.

It’s possible that the influx of people to short-term plans in the coming years might come in large part from this group, but it’s also possible that there may be some significant drain from the existing unsubsidized individual market. And the revised projection that HHS included in the final rule indicated that the majority of the new short-term enrollees in 2019 were expected to be migrating from the individual market (500,000 out of 600,000 people, including both on- and off-exchange enrollees who were expected to transition to short-term plans).

HHS acknowledged that the people who are likely to switch to short-term plans will primarily be young and healthy. As a result of the sicker, older risk pool that will remain in the individual market, premiums will rise over time (more than they would have if the healthy people had stayed in the pool), which will in turn cause premium subsidies to grow.

HHS projects that total federal spending on premium subsidies over the coming decade will be $28.2 billion higher than it would have been if short-term plans hadn’t been expanded. But HHS also notes that another analysis, conducted by the Urban Institute, projects a net savings for the government, due to a reduction in the total number of people who will claim premium subsidies. (The study indicated that 70 percent of the people who would leave the individual market to buy short-term plans would have been paying full price, but that 30 percent would have been receiving premium subsidies, which the federal government would no longer have to pay after the person switches to a short-term plan.)

Longer coverage? It’s still short-term.

It should go without saying that short-term plans with longer duration are still short-term health plans. If you buy them as an Obamacare “replacement,” you’re fooling yourself – because they don’t closely resemble ACA-compliant coverage:

They don’t cover pre-existing conditions, aren’t available at all to people with serious pre-existing conditions, impose maximum benefit limits, and don’t cover all of the essential health benefits. (Maternity care, prescription drugs, preventive services, and mental health/substance abuse care are often not covered by short-term plans). And although all health insurance policies come with a list of things that aren’t covered, the exclusion list tends to be longer for short-term plans. [Note that there are some exceptions, and some states have been working to create better short-term plans: Idaho and Nebraska are examples.]

And the termination of a short-term plan does not trigger a special enrollment period in the individual market, so people who develop a pre-existing condition while covered under a short-term plan could find themselves out of luck if their short-term plan terminates at a time other than the end of the year (and doesn’t include a guaranteed renewability provision), since they won’t be able to get a replacement plan until open enrollment, with coverage effective January 1.

Some coverage beats no coverage.

Having the option to buy longer short-term plans will undoubtedly be welcome news to consumers who already feel as though short-term plans are their only affordable option.

These buyers include individuals and families who are trapped in the Medicaid coverage gap because their states have rejected federal funding to expand the ACA, as well as people who earn less than 400 percent of the poverty level but are denied subsidies due to the family glitch. They also include people who are healthy and who earn just a little bit too much to qualify for premium subsidies (here’s more about how some people miss out on subsidies due to ACA’s subsidy cliff).

But if you’re eligible for premium subsidies in the exchange (or even if you’re not but you feel like you can still manage the cost of a regular plan), an ACA-compliant plan will be your best choice. If you’re eligible for premium subsidies, you might find that you can get ACA-compliant coverage in the exchange for much less than you expect in terms of after-subsidy premiums, due to fact that the cost of CSR is now being added to silver plan premiums in most states, resulting in much larger premium subsidies and lower after-subsidy premiums.

But it’s also worth noting that short-term plans resemble in many ways the regular individual market plans that were available in many states before the ACA reformed the individual market. Those plans weren’t ideal, which is why the ACA was needed in the first place. But in most cases, they provided decent coverage to people who were healthy when they enrolled and then found themselves with unexpected medical costs.

If you’re uninsured (or planning to drop your coverage because you can’t afford the rate increase for next year) and you know that you’re not eligible for a premium subsidy, check to see what short-term plans are available in your area. Know that despite their drawbacks, coverage under a short-term plan is absolutely preferable to being uninsured.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.