Key takeaways

- The House of Representatives has passed the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (H.R. 1319).

- The legislation is likely to help nearly 12 million current marketplace plan buyers, plus more who will newly enroll.

- Under H.R. 1319, no one would pay more than 8.5% of their income for a benchmark plan – including enrollees with household income above 400% of the poverty level.

- The size of subsidy increases would depend on location, income, and age of the policyholders.

- The legislation's adjustment to subsidy guidelines would be retroactive to January 2021, but also temporary, extending only through 2022.

Edit, August 2022: The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), signed into law in August 2022, extends some of the ARR's subsidy enhancements through 2025. Under the IRA, the "subsidy cliff" will continue to not exist through 2025, meaning that premium subsidies will be available even if your income is above 400% of the poverty level (depending on how much the benchmark plan costs relative to your income). And also through 2025, the ARP's subsidy structure will remain in place, meaning that marketplace enrollees will pay between 0% and 8.5% of their income for the benchmark plan.

Edit, September 2, 2021: The subsidy enhancements described in this article were fully implemented by April 2021 in most states, although some of the state-run exchanges took a little longer to get them up and running. For anyone who was enrolled in a marketplace plan prior to that, the additional subsidies are retroactive to the start of 2021 (or the date that the person enrolled in marketplace coverage, if that was after the beginning of the year). The retroactive subsidies can be claimed on 2021 tax returns. Here are some more recent articles we've written about the subsidy enhancements:

- Income cap for subsidy eligibility eliminated through the end of 2022.

- Percentage of income people have to pay for the benchmark plan has been significantly reduced through the end of 2022.

- People receiving unemployment benefits in 2021 are eligible for premium-free benchmark plans and full cost-sharing reductions, through the end of 2021.

- A COVID/American Rescue Plan special enrollment period ran through August 15, 2021 in most states, but is still ongoing in a few states that run their own exchanges.

Edit, March 12, 2021: The Senate passed H.R.1319 on March 6, and the House passed the bill again on March 10. President Biden signed it into law on March 11. CMS published some initial information for marketplace enrollees on March 12.

Obamacare subsidy calculator *

H.R. 1319 is now under consideration in the Senate, so we don’t yet know exactly what will be included in the final legislation. But the health insurance provisions in the House version of the legislation are unchanged from what the House Ways and Means Committee had initially proposed, and have not been sticking points for the bill thus far.

Several provisions in H.R. 1319 are designed to make health coverage more accessible and affordable. Today we’re taking a look at how the legislation would change the ACA’s premium subsidy structure for 2021 and 2022, and the impact that would have on the premiums that Americans pay for individual and family health coverage.

Help for 12 million marketplace enrollees, plus more who will newly enroll

If you’re among the 12 million people who purchase ACA-compliant coverage in the health insurance marketplaces, your coverage is likely to become more affordable under H.R. 1319.

What's more, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that an additional 1.7 million people – most of whom are currently uninsured – would enroll in health plans through the marketplaces in 2022 as a result of the enhanced premium subsidies.

No one would pay more than 8.5% of their income for the benchmark plan

Some opponents of the legislation have criticized its premium subsidy enhancements as a handout to wealthy Americans. But that’s only because the legislation is designed to remedy the subsidy cliff – which can result in some households paying as much as half of their annual income for health insurance premiums. It's a situation that's obviously neither realistic nor sustainable for policyholders.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) only provides premium tax credits (aka premium subsidies) if a household’s ACA-specific modified adjusted gross income doesn’t exceed 400 percent of the federal poverty level. For 2021 coverage in the continental U.S., that’s about $51,000 for a single person and $104,800 for a family of four. Depending on where you live, that might be a comfortable income – but not if you have to spend 20, 30, 40 or even 50 percent of that income on health insurance.

H.R. 1319’s adjustment to the premium tax credit guidelines would temporarily – for this year and next year – eliminate the income cap for premium subsidies. That means that – regardless of income – no one would have to pay more than 8.5 percent of their household income for the benchmark plan (the second-lowest-cost Silver plan available in the exchange in a given area).

Under this approach, subsidies would phase out gradually as income increases. Plan buyers would not be eligible for a subsidy if the benchmark plan’s full price wouldn’t be more than 8.5 percent of the household’s income. But in some areas of the country – and particularly for older applicants, who can be charged as much as three times the premiums young adults pay – premium subsidy eligibility could end up extending well above 400 percent of the poverty level.

In addition to addressing the subsidy cliff, H.R. 1319 also enhances premium subsidies for marketplace buyers who are already subsidy-eligible. The subsidies would get larger across the board, making after-subsidy premiums more affordable for most enrollees. At every income level, the legislation would reduce the percentage of income that people are expected to pay for the benchmark plan, which would result in larger subsidies.

Larger subsidies? Here are a few examples.

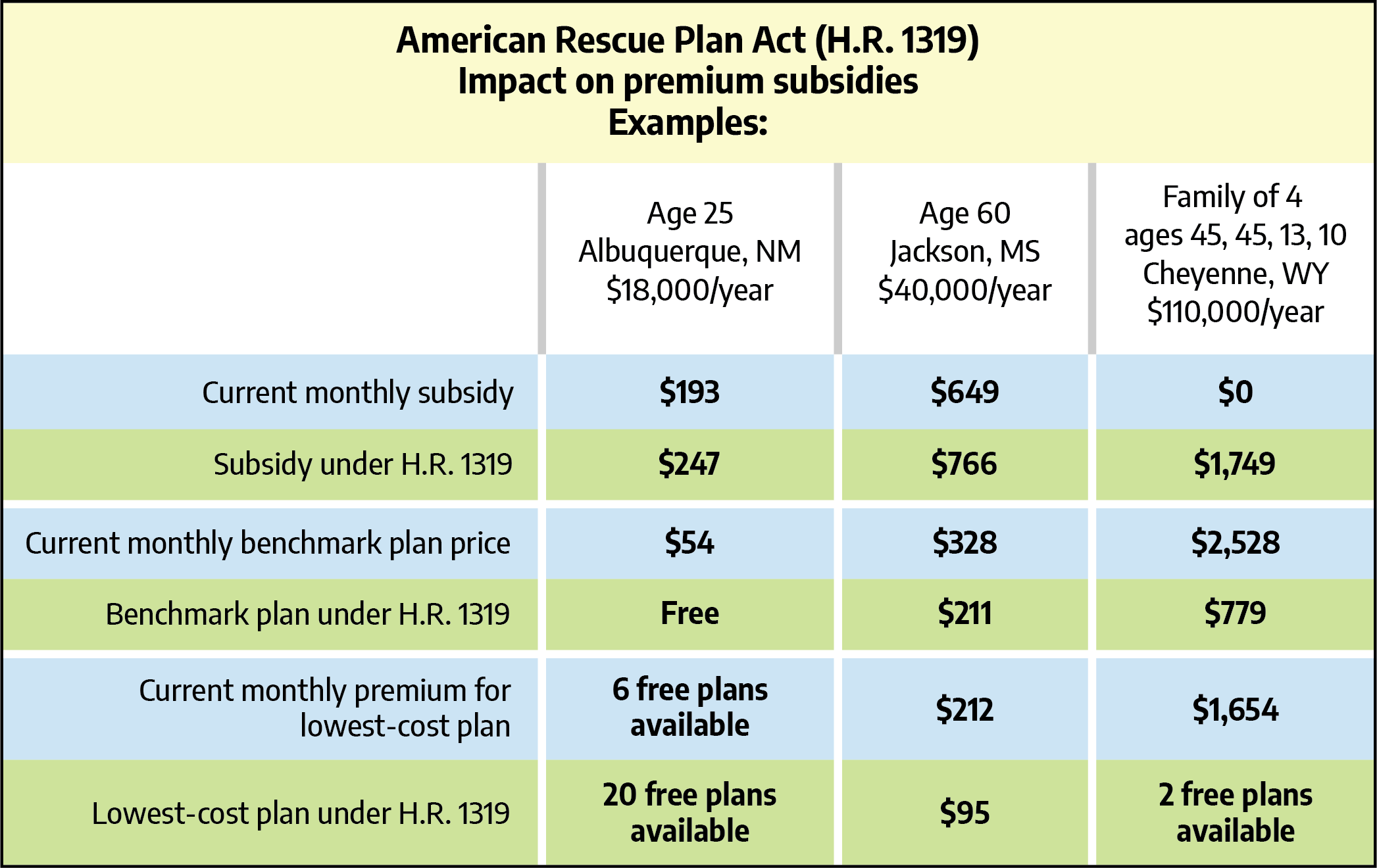

How much larger? It would depend on location, income, and age. Let’s take a look at some examples.

We’ll consider applicants with various income levels and ages in three locations: Albuquerque, New Mexico – where premiums are among the nation’s lowest; Jackson, Mississippi – where premiums are close to the national average; and Cheyenne, Wyoming – where premiums are among the nation’s highest.

In each location, we’ll see how things would play out for a 25-year-old, a 60-year-old, and a family of four (45-year-old parents, and kids who are 13 and 10), all at varying income levels.

You can see the full comparison in this spreadsheet. (Current premiums were obtained via HealthCare.gov's browsing tool. Premiums under H.R. 1319 were calculated using the proposed applicable percentage table in Section 9661(a) and the methodology outlined here, which would be unchanged under the new legislation.)

You can see the full comparison in this spreadsheet. (Current premiums were obtained via HealthCare.gov's browsing tool. Premiums under H.R. 1319 were calculated using the proposed applicable percentage table in Section 9661(a) and the methodology outlined here, which would be unchanged under the new legislation.)

In most cases, you'll notice that the subsidy amount is larger under H.R. 1319, resulting in a lower benchmark premium and also a lower price for the lowest-cost plan available to that applicant (or more plans available with no premium at all). This is because the new legislation specifically reduces the percentage of income that people have to pay for the benchmark plan. That, in turn, drives up the subsidy amounts that are necessary to reduce the benchmark premium. And since premium subsidies can be applied to any metal-level plan, it also results in a lower cost for the other available plans (or more premium-free plans, depending on the circumstances).

As you consider these numbers, note that if the current subsidy amount is $0, either the benchmark plan is already considered affordable for that person, or their income is over 400 percent of the poverty level and subsidies are simply not available. If the subsidy amount is $0 under the H.R. 1319 scenario, it means that the benchmark plan would not cost more than 8.5 percent of the applicant’s income.

As you can see, the additional subsidies would be widely available, but would be more substantial for people who are currently paying the highest premiums. Under the current rules, it may not be realistic for our Wyoming family to pay more than $30,000 in annual premiums (enrolling in the benchmark plan, with premiums in excess of $2,500 per month). The American Rescue Plan Act would bring their annual premiums for the benchmark plan down to under $10,000, which is much more manageable.

The legislation is not, however, a giveaway to wealthy Americans. If that family earned $500,000, they still wouldn’t get a premium subsidy under H.R. 1319, because even at $2,528/month, the full-price cost of the benchmark plan would only amount to 6 percent of their income. Unlike Medicare and the tax breaks for employer-sponsored health insurance, financial assistance with individual market health insurance would not extend to the wealthiest applicants.

By capping premiums at 8.5 percent of income, H.R. 1319 provides targeted premium assistance only where it’s needed. And by enhancing the existing premium subsidies, the legislation makes it easier for people at all income levels to afford health coverage.

Premium enhancements would be retroactive but also temporary

Assuming these premium subsidy enhancements are approved by the Senate, they’ll be retroactive to the start of 2021. Current enrollees will be able to start claiming any applicable extra subsidy immediately, or they can wait and claim it on their 2021 tax return. The additional premium subsidies would also be available for 2022, but would no longer be available as of 2023 unless additional legislation is enacted to extend them.

And there’s currently a special enrollment period – which continues through August 15 in most states – during which people can sign up for coverage if they haven’t already. In most states, this window can also be used by people who already have coverage and wish to change their plan, so this is definitely a good time to reconsider your health insurance coverage and make sure you’re taking advantage of the benefits that are available to you.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.